A Tribute to Sheri S. Tepper's Speculative Fiction

Written in 2016-17, republished here in connection with Webs

I spent quite a few years hanging out at Mike Glyer’s File 770 (a news ‘zine) with the community at during and after the years when the Sad and Rapid Puppies were trying to drive the “woke” out of the SFF Hugo Awards (read: too many people who were NOT straight white Christian men were winning the awards) back in the day. It was the usual story: I started reading, got involved, started replying to the posts and to other fans hanging out there, and next thing I know, started sending a few things to Mike to post if he wished.1

I was reminded of this piece about my readings/changing responses to Sheri S. Tepper’s work today when I was editing my “presentations and publications” from my CV. I took a look at it and went, holy shit, here’s this piece I wrote about eight years ago about my different perspectives on a feminist writer’s work as my knowledge of different feminist theory changed/increased over time, and, well, somehow this struck me as fitting in with the Webs Book which is about feminist receptions (including but not limited to my own) of Tolkien’s work. So, I thought I’d bring it over here to avoid forgetting about it again!

The piece got some lovely feedback from others sharing their ideas about Tepper’s work which you can read at the link to File 770 above. And I can highly recommend Mike’s ‘zine as an incredible resource for news about all aspects of sff fandom (not to mention a incredibly maintained tagging/curating system that makes it easy to find stuff again!).

The connection(s) I saw involved reader response as a mode of criticism especially involving feminisms. About six of the Webs by Women posts have been about feminist topics of various sorts, but mostly looking at various definitions in different contexts, academic and otherwise. I’m still thinking about how to integrate my journey through different feminisms and their impact on me. I found Tepper’s work during a period after I’d left academia (due to sexism and misogyny) and was reading only women writers (in my late 20s), thus in what I now call my “angry young feminist” phase, a period during which I’d stopped re-reading Tolkien’s fiction (because I didn’t want to get mad at a story that was so important to me for so long; as I discuss elsewhere in this Substack, I got over it!). In terms of Tepper (born in 1929, working at Planned Parenthood, and her eco-feminism), I see commonalities between us in terms of Second Wave feminism.

Now, when I talk about feminist approaches, especially in the context of Tolkien studies, I am now interested in intersectional feminisms. One of the best intersectional feminist Substacks is one titled, feminism for all by 𝙅𝙤 ⚢📖🏳️🌈. Since I plan to write the Webs book for a popular/general audience (and writing pieces for File 770 gave me a chance to practice some different rhetorical choices), I am trying to find sources to cite that one, are not as academically weighted down as sometimes happens with peer-reviewed publications, and two, are accessible online which often does NOT happen with peer-reviewed publications.

In a stack titled “bell hooks & beyoncé: who gets to call themselves a feminist?” 𝙅𝙤 ⚢📖🏳️🌈 summarizes bell hooks’s definition of feminism; hooks’s 1984 book, Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center was the first work I read in my doctoral program that criticized the extent to which the major Second Wave feminist writers (white, middle-class, mostly heteronormative) had theorized sexism/misogyny as the “original sin” that was the basis for all other oppressions. In contrast hooks, as 𝙅𝙤 ⚢📖🏳️🌈 argues, points out that “these [feminists] were not global south/majority nor women of color asking to center sexism above other oppression. We do not have that luxury, that privilege is not ours.”2

One key point is the difference between “feminism” as an identity (resulting in a binary), and “feminism” as advocacy, movement, action (and especially the usefulness of plural nouns, i.e. feminisms, to avoid privileging one type of feminism which is usually default/white/middle/class version).

If you’ve not heard of Sheri S. Tepper (something which happens to me quite often the older I get—that the sff writers I adored in my youth have fallen out of print, or are not much noticed in the growing number of sff books!), here is an essay, “In Memoriam: Sheri S. Tepper” (Science Fiction & Fantasy Writer’s Association), about her life.

I wrote the following essay as a tribute to her work.

NOTE: Spoilers for a number of Tepper’s novels occur throughout the essay.

CONTENT WARNING: For references to rape and abuse of young women as an element of Tepper’s novels.

The Fan

I found my first Tepper novel in the early 1980s. I remember standing in the University of Washington bookstore reading the opening pages of King’s Blood Four, the first of what would become the nine-novel triple trilogy The True Game. Had Tepper’s work continued in that vein, interesting world-building with a male protagonist, I am not sure I would have become such a fervent fan.

However, even this early novel had threads of the feminist themes Tepper would develop in more detail in her later work. Peter starts out as a typical fantasy orphan hero. He is a young man, a foundling, raised in an all-male environment, who almost immediately embarks on a quest. The setting is the world of the True Game where characters have fantastic powers echoing medievalist fantasy conventions. But the initiating event is an attack on King Mertyn in which Peter is used and injured by his male lover, and the outcome of Peter’s journey is learning about the Immutables (those outside the Game who lack any of the powers valued in the Game) and meeting his mother (not his father!). Those differences were different enough to keep me reading the trilogy and keeping an eye out for her other work.3 I was lucky that she published so many novels so quickly: her entry in Wikipedia lists ten novels published in 1983-1985.

The later trilogies in the True Game series, Mavin’s and Jinian’s, turn away from the male bildungsroman to twist fantasy conventions on multiple levels. Suddenly, as with Anne McCaffrey’s Pern series, I found myself in a science fiction narrative of sorts, a lost colony settled by humans with all knowledge of their origins and history being buried and more fantastic elements replacing them.

But even before I read the later trilogies in the True Game series, I found the Marianne Trilogy.4

Reading the first in this series put Tepper’s name immediately on my “buy as soon as they appear” list of authors, and that response never changed although some of her later works appeal to me much less than the earlier ones. I tend to be completist when I love an author’s works even if I do not love all of them.5

The opening paragraph of Marianne, The Magus, and the Manticore remains one of my favorites:

During the night, Marianne was awakened by a steady drumming of rain, a muffled tattoo as from a thousand drumsticks on the flat porch roof, a splash and gurgle from the rainspout at the corner of the house outside Mrs. Winesap’s window, babbling its music in vain to ears which did not hear. “I hear,” whispered Marianne, speaking to the night, the rain, the corner of the living room she could see from her bed. When she lay just so, the blanket drawn across her lips, the pillow crunched into an exact shape, she could see the amber glow of a lamp in the living room left on to light one corner of the reupholstered couch, the sheen of the carefully carpentered shelves above it, the responsive glow of the refinished table below, all in a kindly shine and haze of belonging there. “Mine,” said Marianne to the room. The lamplight fell on the first corner of the apartment to be fully finished, and she left the light on so that she could see it if she woke, a reminder of what was possible, a promise that all the rooms would be reclaimed from dust and dilapidation. Soon the kitchen would be finished. Two more weeks at the extra work she was doing for the library and she’d have enough money for the bright Mexican tiles she had set her heart upon. (1).

This scene is vital, so present in its appeal to the senses (the sounds of the rain—a sound I often lie awake listening to—the light reflecting off bookshelves, a “refinished table,”), that I become immersed in the world immediately. Marianne’s achievements differ greatly from those of most fantasy novels: she is remodeling an old house and refinishing furniture primarily through her own labor in order to reclaim the color and feel of her childhood home, lost with her parents’ death. [ETA: Over the course of the trilogy, she gains her own powers which can be categorized as more religious (but not Christian) in nature.] The fantasy worlds in this trilogy seem unique (even in the context of Tepper’s work), and I fell in love.

I loved and still love Marianne and her momegs, Marjorie and her horses (Arbai series), Mavin’s refusal to compromise (Mavin trilogy), Jinian and her animals, Jinian’s Seven (Jinian’s trilogy), and the Seven–Carolyn, Agnes, Bettiann, Ophelia, Jessy, Faye, and Sova—in Gibbon’s Decline and Fall.

I love Tepper’s world-creation, the animism and ecological/environmentalist themes in her work, the creativity of her names for characters and animals, and, most of all, her descriptions of trees and forests. Tepper and Tolkien’s work seem so alike to me in their love for trees although I wonder how many readers would see any similarity.

I love the feminist elements (some of them!): my love for Grass is not only because of Marjorie and her horses but because of Marjorie’s quest to save her daughter. An additional feminist element (which I had not thought of until the early drafts of this essay) are some of the male characters who do not fit the model of heroic [AKA toxic] masculinity: there are two of them in Grass (Rillibee Chime and Brother Mainoa).6

I also (and I’ve not seen many reviews talking about this element!) love the skewering of academia that Tepper does in some of her novels (notably in the True Game series and in Sideshow (third of the Arbai series).

The opening paragraphs of Chapter 1 of Grass are also very high on my list of favorite openings (I did a presentation on the novel as a feminist epic revision of Dune by in part focusing on the epic structural elements such as this opening!)

Grass!

Millions of square miles of it; numberless wind-whipped tsunamis of grass, a thousand sun-lulled caribbeans of grass, a hundred rippling oceans, every ripple a gleam of scarlet or amber, emerald or turquoise, multicolored as rainbows, the colors shivering over the prairies in stripes and blotches, the grasses—some high, some low, some feathered, some straight—making their own geography as they grow. There are grass hills where the great plumes tower in masses the height of ten tall men; grass valleys where the turf is like moss, soft under the feet, where maidens pillow their heads thinking of their lovers, where husbands lie down and think of their mistresses; grass groves where old men and women sit quite at the end of the day, dreaming of things that might have been, perhaps once were. Commoners all, of course. No aristocrat would sit in the wild grass to dream. Aristocrats have gardens for that, if they dream at all.

Grass. Ruby ridges, blood-colored highlands, wine-shaded glades. Sapphire seas of grass with dark islands of grass bearing great plumy green trees which are grass again. Interminable meadows of silver hay where the great grazing beasts move in slanted lines like mowing machines, leaving the stubble behind them to spring up again in trackless wildernesses of rippling argent (1-2).

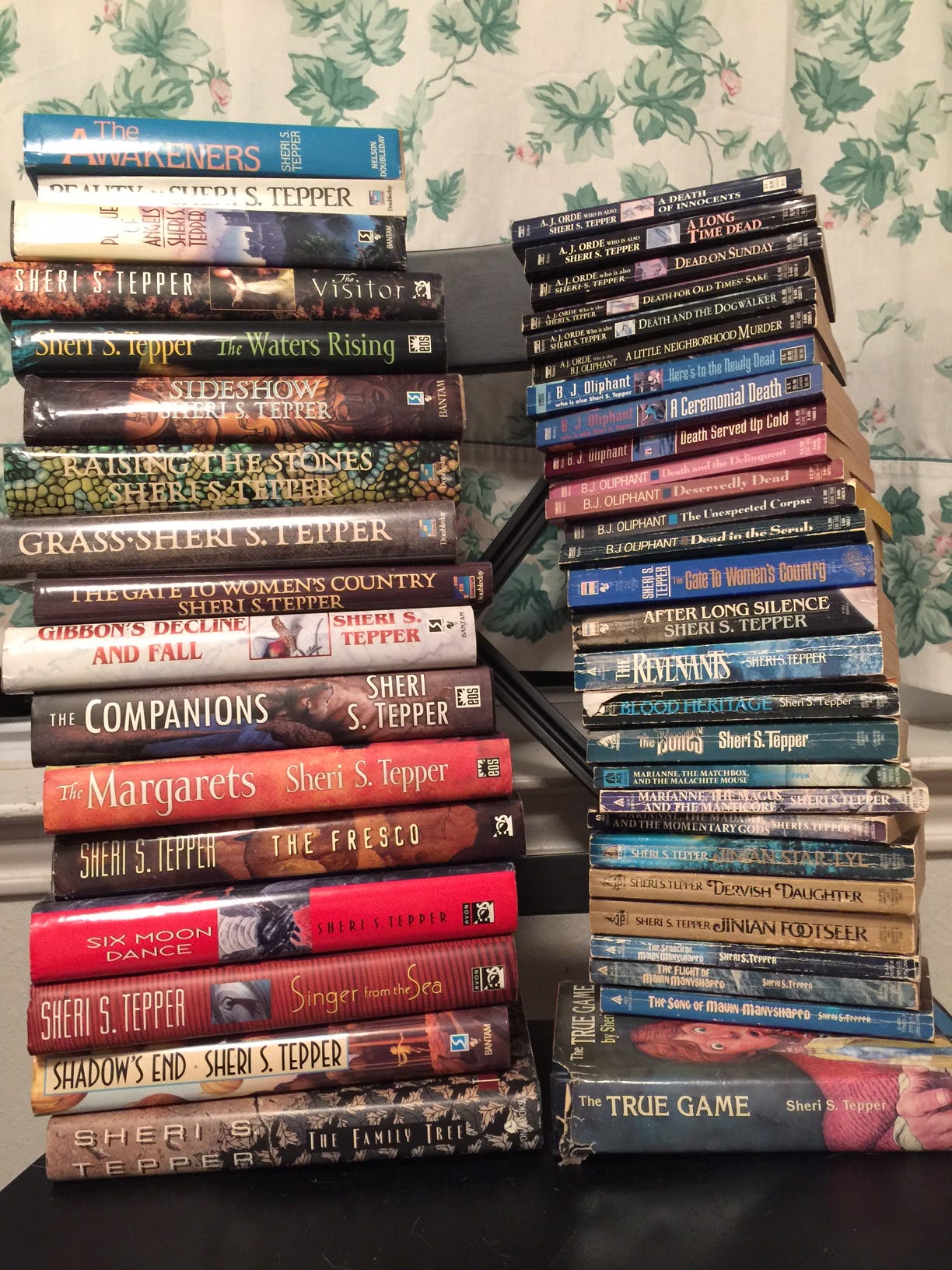

Tepper’s books occupy a major part of my “favorites” bookshelves (the ones in my bedroom as opposed to the ones in the library or in my home office or in my office at school). I took this picture of her books stacked up on my bedroom chair the day after I heard of her death.

I wrote Mike to ask if he would be interested in a tribute essay when I learned Sheri Tepper died (October 22, 2016). I began scribbling notes and re-reading some of her books immediately. I got (immediately!) sidetracked (academic habits now ingrained), looking at the scholarship and some critical discussions of her work online. I kept writing, and cutting, and cutting, and writing, until I realized there was a huge amount I wanted to say that I did not have time for and could not yet develop at this point.7

My original impulse was to write a fan tribute, but apparently, I am a different kind of fan in 2016 than I was in 1986.8 I still love (some) of Tepper’s work passionately (and find I am immediately grabbed/immersed in my favorites the moment I open them and read the first paragraphs) even though I can see the validity of many of the criticisms I’ve read. It’s nothing as simple as the suck fairy visiting loved books from my early years (I’ve been reading Tepper, like my other favorite writers, more or less continuously since I found her work thirty-four years ago [42 now!]).

I haven’t yet figured out what has happened although I am beginning to think that the flaws in her work are representative (for me) of some of my own flaws, and some of the flaws in some feminist discourses, and even in the broader American culture. To figure that out, I have to write more, but that has to come later. It’s all connected to my life and experiences, and to the development of Anglo-American feminist speculative fiction and to the current political situation in the U.S.

I wrote the first draft of this piece Wednesday, November 9, nearly twelve hours after it became clear that Donald Trump would win the presidency. The weeks since then have featured events that I think go well beyond what Tepper in even her most “heavy-handed”9 message fiction thought of writing even though her focus on the dangers of patriarchal authoritarianism, particularly that flavored by a certain flavor of American evangelical fundamentalism (similar to that of the Quiverfull Movement), seems prescient to me.

For some years, I have thought that Tepper, among all the sff writers whose work I know, was the most focused on detailing the threats to women’s rights, especially the right to reproductive choice, that have been the focus of the GOP/Tea Party/social conservative movement the past few decades and which are reading unprecedented heights.10 These attacks are not the only threats from the social conservatives/GOP who are exulting in the chance to dismantle the legislation and overcome court rulings that addressed systemic sexism, racism, homophobia, and poverty in this country, but I do not see much contemporary sff addressing this particular issue.11 Tepper’s work is informed by the feminist discourses that are labelled “Second Wave Feminism,” a focus I see as connected to the strengths of her work as well as its flaws.12

One of the quotes from her 2008 interview at Strange Horizons is very much reflective of what I’ve been feeling since the election:

SST: Post-apocalyptic, post- or mid-holocaust? You say that’s a grim place to go on a daily basis, yet we both do it every day, don’t we? We’re living in it, Neal. Did you think it was still in the future? Read the daily paper. How do I hold myself there? I read the daily paper. How do I recover? I don’t. Do you?

I discovered Tepper, as I found so many other women writers, after I left academia in 1982 because of the sexism in a graduate theatre program where I was doing a Master’s in playwriting.13 Some of my experiences in that graduate program, and in others, are why I do not see all of Tepper’s male antagonists as “straw-men” or unrealistically flat. I spent several years working in low-level clerical jobs and adjunct teaching while reading nothing but feminist theory and women writers. I started by finding and reading all the writers discussed in Joanna Russ’ brilliant How to Supress Women’s Writing, but I also pursued a longtime strategy of mine that predated my becoming a feminist: read the bookshelves at libraries and bookstores. If a title or a cover caught my attention, I’d read the first page and see what if it grabbed me.

That’s how I found Tepper.

At the time, I was happy to see the feminist ideas in her work and did not see some of the more problematic aspects relating to Second Wave feminism, particularly in regard to the whiteness of her characters and a view of sex / gender / sexual orientation that defaults to straightness and erases or condemns queerness, flaws that [ETA: were typical at the time in most cultural productions and continued into the 21st century as debates in sff fandom the past few years have highlighted].

I returned to academia in the late 1980s because I could do feminist work in a doctoral program; I did not realize how much intersectional feminist work had been done during the 1970s/1980s until I took my first theory course. That course, and the ones following, changed everything for me. Among other things, critical theory freed me from the limitations of the New Criticism methods I learned in my undergraduate days (which excluded popular genres by fiat): Foucault was the one whose work gave me my first tools for writing about science fiction in an academic context (though I had to sort of sneak it into my dissertation). The work by intersectional feminists gave me an entirely different perspective on the sff I loved.

The Academic

As a lifelong fan turned academic who got a Ph.D. in English in part so I could teach sff, I have always been aware of how literary canons are built to exclude. The exclusionary nature of canon-building did not disappear when the 1970s led to so many challenges to the Anglo-American canon of literature: what came about was more an “explosion” of canons [ETA: something that is still bothering the hell out of the “Western Civilization/Dead White Male Canon” defenders and has started being imposed by fiat at some universities.]

Thus, there is a feminist sf canon that developed over time, with scholars focusing until recently on the relatively small body of text known as the “seventies feminist utopias” (or the lesbian separatist utopias). Feminist sf scholarship has grown and developed in recent years, and I think the early focus on utopias/dystopias was inevitable given that utopias/dystopias were the only “science fiction” allowed in literary studies at the time.14 I love some of the novels (particularly those by Joanna Russ and Marge Piercy), but never felt that I had much of anything to say about them as opposed to work by other women sff writers that I saw embodying various feminist ideas in the more genre-typical works.

My love for Tepper’s work was one of the main reasons that I became interested in the ways in which (some) women writers publishing in the 1980s integrated feminist ideas into their sff in ways that differed from the 1970s feminist utopias (a genre which has nearly disappeared, as Peter Fitting discusses in his excellent essay, “Reconsiderations of the Separatist Paradigm in Recent Feminist Science Fiction,” published in Science Fiction Studies in 1992).

The Marianne trilogy, along with Mavin’s and Jinian’s, and the Arbai series (Grass, Raising the Stones, and Sideshow are my favorite Teppers.15 My first major academic presentation in 1991 was on Grass as feminist epic revision of Frank Herbert’s Dune. I have published one article on Tepper’s work in which I talk about the trilogies in the context of feminist utopias, arguing that Tepper’s work explores feminist themes through the concept of “momentary utopias” or “momutes.”16 The paragraphs below cover some of points I made in that publication.

The early trilogies (Marianne’s, Mavin’s, and Jinian’s) are all stories about young women who resist the expectations of their male-dominated families and cultures in ways that differ from the 1970s feminist utopias (with the exception of Woman on the Edge of Time). Since more women began publishing in the 1980s, a greater range of feminist ideas began to appear along with a greater range in genres. Tepper did write one book that can arguably be considered a feminist utopia or dystopia (The Gate to Women’s Country) but I consider most of her work to be feminist speculative fiction with strong fantastic/fantasy elements.

The blend of fantastic worldbuilding and systems of magical powers existing with stories of male family members raping girls, restricting their education, and forcing them into marriages inform these novels. The protagonists resist/escape family pressures but focus on individual resistance for the most part. All the protagonists escape their families but only one is involved in an attempt to change the dominant culture.

Marianne changes her life by changing the time-line (with the help of the momentary gods which she learns how to use by watching her aunt, the villain of the narrative) rather than by changing social expectations or cultural systems. Her power comes from her birth as a Kavi, a member of the hereditary ruling class in Alpenlicht. This trilogy stands out as one of the few of Tepper’s stories in which heterosexual marriage is presented as a positive relationship. I loved it for its worldbuilding, the momegs, the beautiful descriptive prose of the natural world, and the secondary worlds.

Mavin is born into an oppressive extended family, a group of Shapeshifters in the Land of the True Game. Mavin escapes by leaving the Shifter compound, rescuing her younger brother, and, much later, her older sister, and others along the way. Not only does she face rape as she as she is deemed adult (is able to Shift), but the ongoing rape and abuse of her older sister is revealed which gives her an additional reason to leave. Mavin’s trilogy is very much a quest narrative covering twenty years of her life, but she never marries. She loves Himaggery, a wizard she meets in the first novel, but does not stay with him. One of her quests is to rescue him, and shows that they were happy only when shifted into magical beasts (singlehorns are described as very similar to unicorns). Mavin gives their son, Peter, to her brother to raise. Mavin does not change the cultures or communities she passes through, but she goes beyond what Marianne does by rescuing women and girls. The extent of the world beyond the Land of the True Game is shown in Mavin’s journeys—and the environmentalism/ecological elements are very strong.

Jinian’s trilogy moves from the focus on the individual to that of the groups attempting to change the dominant culture before the world dies (because of the actions taken by human colonists). On her quest, Jinian learns about the origin and history of human settlement on Lom. Humans colonized the planet, not realizing that Lom (embodying the Gaia hypothesis) was sentient and able to communicate with all its native creatures. Lom tries to bring humanity into its web, but humans resist; then, Lom grants humans magical Talents. But their increased power leads to more violence against each other and the destruction of the environment. The groups working to try to change human society, the Wizards and Dervishes specifically, are mostly (but not exclusively) women.17

Jinian is raised in an abusive family (who turns out not to be her birth family), but is helped from the start by a group (a coven!) of older women, called a Seven, who are Wizards /Wize arts. She is a Wizard and a beast-talker, able to communicate with animals and the other sentient beings of Lom. She is the one who discovers that the spirit is trying to commit suicide. As a result of the efforts Jinian leads, Lom decides to live but takes away the humans’ Talents. Jinian becomes involved with and marries Peter during the course of her quest, but also has strong relationships with other women, not only with her Seven, but with Silkhands the Healer.

Over time, as I read Tepper’s late work in the context of my graduate courses and embarked upon my first attempts to write intersectional feminist scholarship on science fiction [ETA: which is difficult, and I’m still trying to figure it all out!], I became aware of the problematic aspects relating to race and heteronormativity. Those patterns are not unique in sff either at the time or today. Additionally, I saw the tendency in Tepper narratives to construct sexism as institutionalized by authoritarian religions and regimes as caused by a genetic component of humanity.18

Thus, her novels showed that only a change in the human genome could change human nature, leading to eugenics/breeding programs (explored in detail in The Gate to Women’s Country but also central to The Waters Rising and Fish Tails). Some novels show groups of humans running the breeding programs while others feature external agents causing the change, at times with the cooperation of some humans (the Goddess in Gibbon’s Decline and Fall, the Arbai device in the Arbai trilogy, the Pistach in The Fresco).19

[ETA: Note to self: need to explore how Benita, the protagonist in The Fresco, and Faye, one of the Seven in Gibbons, are women of color (Hispanic and African American, respectively) and what, if anything has been written about them].

The Question for the Future

I am ending this piece by noting the question that I keep coming to as I’ve been working on the drafts: the extent to which Tepper’s gender/genetic essentialism is representative of popular ideas in feminism specifically and more broadly in U.S. culture.

The entry on Feminist Perspectives on Sex and Gender (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) covers some of the feminist theories which are are essentialist (meaning the assumption that sex or gender differences are “natural,” or genetically created).

P. Z. Myers noted in a recent post in his blog, the idea that “male” and “female” DNA exists is so widespread that even a Young Earth creationist cites “science” (incorrectly, but still tying the claim to “scientific knowledge”) to support his claim of the essential differences between men and women: There’s no such things as male and female DNA by P. Z. Myers.

Genetic essentialism is heavily implicated in Jim Crow concepts of “race.”20 This conversation between two anthropologists, (which Myers linked to in another blog post) covers the widespread and common understanding that DNA is “race”: New Articulations of Biological Difference in the 21st Century: A Conversation, Agustin Fuentes and Carolyn Rouse, at Anthropology Now.

Agustin: The core problem here remains that biology courses in high school and college are taught by individuals who, at least subconsciously, buy into the “race as biology” and “genetics as deterministic” perspectives. There are very, very few high schools in the United States where accurate information on human biological diversity is offered. There are few courses even at the college level where such information is provided or where contemporary evolutionary theory and biology are the norm. Inside and outside the classroom, students are mired in implicit “race talk” related to issues of biology and an overemphasis on genetic control of behavior. Think about discussions of professional sports, testosterone, violence, sexuality.

The history of deterministic genetics is tied to the history of genetics, with the impact on popular understanding of sex, race, and sexual orientation being documented fairly extensively.21 The tendency to assume a “natural” (aka genetic) cause for differences is widespread.

Tepper’s work definitely assumes a genetic component, but stories/novels are sneaky. They twine around and bite their own tails. As I was re-reading Tepper’s work for this essay, I kept thinking about how Fish Tails, unlike some of the earlier novels, seems to critique the common trope of breeding programs as solutions in the two plot lines: Lillis and Needly’s life in Hench Valley, one of Tepper’s most clearly delineated (and yes, heavy-handed!) portrayals of patriarchal authoritarianism, and Xulai’s story (which began in The Waters Rising. I agree with the various critical reviews I’ve seen that this trilogy has a number of problems in narrative technique, characterization, and themes,22 but it also contains some criticism of the attempt to improve the human race through breeding programs that did not exist in the earlier works.

So this piece seems to be the start of something longer trying to figure out what I see going on in Tepper’s work, and how people (including but not only me) have responded to it over the years. I don’t really need any more projects added to the mountain, but I don’t think this one is going to go away anytime soon.

ADDENDUM July 4, 2025: Well, technically it did go away, for a while, in that I didn’t keep working on it after it appeared at File 770. The drafts and other process materials are lurking in my personal archive of publications. But now I’ve gotten my hands on it again and dragged it back into my Web, I might use parts of it in the actual book, or I might develop some of it into its own essay. I gave a number of presentations on her work back in my feminist speculative fiction period.

"Writing Against the Grain: T. Kingfisher's Feminist Mythopoeic Fantasy," File 770, Aug. 4, 2021. If you haven’t read Kingfisher, why not? And why not start now????

"Visiting Middle-earth," File 770, July 5, 2018. A description of the trip we took to see Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth at the Bodleian (and some other stuff!).

From 𝙅𝙤 ⚢📖🏳️🌈’s feminism for all: what follows is an excerpt quoted from the longer stack (which also includes block quotes from the original): Substack’s tools for indicating block quotes are rather limited, so I use the green block to highlight 𝙅𝙤 ⚢📖🏳️🌈’s words; the blocked quotes from Lorde and hooks’s work have the original bolding:

When bell hooks wrote Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism at the age of nineteen, and followed it up with Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center in 1984, she set out to redefine the feminism that middle class, white, heteronormative feminists had made their own, and exclusively their own. That was a feminism that argued that all women were oppressed. It argued, as a handful of woman have argued to me, that misogyny is the original sin, the great oppression from which all other oppressions grow, the blueprint for racism, xenophobia and colonialist thinking, religious discrimination, classism, homo/transphobia…

Needless to say, but I’ll say it anyway: these were not global south/majority nor women of color asking to center sexism above other oppression. We do not have that luxury, that privilege is not ours.

As Audre Lorde wrote, in her essay There is no Hierarchy of Oppression:

I cannot afford the luxury of fighting one form of oppression only. I cannot afford to believe that freedom from intolerance is the right of only one particular group. And I cannot afford to choose between the fronts upon which I must battle these forces of discrimination, wherever they appear to destroy me. And when they appear to destroy me, it will not be long before they appear to destroy you.

Defining the original sin, the original oppression, is not what we should focus on. The measure of an oppression, the struggle of a single oppression over others, is not irrelevant to the struggle to end oppression and systems of domination. They must all be worked against, the systems themselves must be addressed and taken to task.

For hooks, the definition of feminism is:

Feminism is a struggle to end sexist oppression. Therefore, it is necessarily a struggle to eradicate the ideology of domination that permeates Western culture on various levels, as well as a commitment to reorganizing society so that the self-development of people can take precedence over imperialism, economic expansion, and material desire.3

The repeated use of the word struggle highlights a core tenet of hooks’ feminist philosophy: feminism as action. She wrote that one of the ills of the early second-wave feminist movement was that women, particularly in separatist movements that advocated for women to (unrealistically) live lives apart from men, focused on feminism as identity. A lifestyle choice, the modern equivalent of writing “feminist” in your social media bio. A hot take, a way to align with a certain image. To say I am a feminist turns feminism to a binary, and either/or. Either you prescribe to a particular set of beliefs, or you are not. It doesn’t allow for gradations of definition of feminism, it doesn’t allow that, Angela Davis once wrote, that there are feminism movements instead of a single feminist movement.

One of my favorite parts of Raising the Stones is the way in which the narrative deconstructs the “father quest” in Samasnier (Sam) Girat’s arc. Sam, having been brought up on Hobbs Land after his mother Maire escaped from Ahabar, misses the legends and religion, or his idealization of them, and embodies those ideals in his father. [ETA: When Sam finally does meet his father, he finds out that absolutely nothing of what he had imagined was embodied in the man who had raped his mother, raped others, including beings enslaved on Ahabar, participated in wide-spread terrorism, and regretted none of it. I can see the point others have made about the melodramatic Snidely Whiplash elements of some of Tepper’s male antagonists; on the other hand, their actions are right out of historical rcords and contemporary headlines.]

All cover images come from Amazon entries for the books.

My least favorite work is Beauty (so much so that I don’t think I have ever re-read it), and others that I rarely reread are The Awakeners duology (North Shore and South Shore), The Companions, and Shadow’s End). [ETA: Now when I retired and had to move from a house that had bookshelves five rooms and from my corner office in my department, I had to downsize considerably, a task made easier by the proliferation of e-books which I had been turning to the older I got due to eyesight issues and arthritis in my hands). My favorite hard-copy Teppers are on one shelf of the two bookcases in the single bedroom of my cozy hobbit-hole apartment!]

The major male characters who are antagonists can be described as flat characters/ stereotypical villains (and there are many of them) although I keep thinking of the behaviors Tepper must have observed over her years working at CARE and Planned Parenthood, and of behaviors I experienced growing up in the 1950s/1960s, and stories I heard from my friends and students from the 1970s, to, well, the 21st century!

This reviewer’s comment struck me as revealing: criticizing the characterization of Rigo (especially the sections in which he is the point of view character) in Grass as stereotypical, he ends by saying: Sadly, I’m sure this isn’t too far afield from some real battered spouse situations, but it’s not anything I wanted to read about. Real life may be like this, but if any author is going to put it into a book, I want the catharsis of Marjorie kicking his ass by the end of the novel. [ETA: Russ Albery, “Review: Grass by Sheri S. Tepper, Eyrie). I’m left wondering what he would define as “kicking ass” because Marjorie saves her daughter, saves her horses, convinces the Foxen to intervene to save the colonists, helps solve the mystery of the plague, rejects the handsome younger male who is trying to restrict her to his romantic ideal, boots her Catholic guilt into the gutter, walks away from Rigo and her religion (and the one priest who is trying to keep her controlled), and then leaves for her own quest (bits and pieces of which we get in the other novels in the trilogy) with First (one of the foxen. It may be unfair of me to suspect he wanted her to kill him in some way, but really, the victories Marjorie gains are pretty amazing without falling into the “strong female character” which in the 1970s at least was sort of code for what some of us called “a man with boobs,” i.e. a female character action hero who acted just like the male action heroes. For a fantastic analysis about Marjorie and First and the foxen from the context of interspecies relations, I can highly recommend this 2024 essay which I just found: Ewa I. Wiśniewska, “Interspecies Relations in Grass by Sheri S. Tepper.” Ostrava Journal of English Philology, vol.16, no. 2, 2024-literature and culture.]

One of the ongoing problems in my life although I receive very little sympathy for it (I think it might be a form of hypergraphia although the official Technical info seems to assume that hypergraphia involves hand-written work and repetitive work—so maybe it’s related being an autist.

In 1986, I was just starting my doctoral work which focused on which focused on gender, queer, and critical race theories and was years away from learning how to be a fan of problematic things.

“Heavy-handed” is in quotes because I tend to think one person’s heavy-handed message fic can be another person’s incisive description of reality. Tepper is pretty up-front about preaching in her fiction (and rejecting “literary fiction” as she notes in this 2008 interview. And after two decades of reading (and enjoying but aware of) the “heavy-handed” message science fiction by men about men written for a (perceived to be) male audience, I was pretty happy to find a feminist message back then. [ETA: And now in July 2025, the escalation of the current regime over what happened during Trump’s first term is horrifying.]

If I thought the heights were unprecedented back in 2017, they’re are reaching the next galaxy here in 2025 (I had a link to an article about those attempts, but the link had gone dead, so in lieu of that I’m just going to link to Jessica Valenti’s Abortion Every Day Substack which I read every day (and share every day) because it’s the single best source for comprehensive coverage of the shitstorm of ongoing attempts to strip reproductive rights as well as analysis that I’ve ever found (and since I remember a lot of years where I and others were patronized by being told not to worry our pretty little heads that Roe guaranteed our rights, well, yeah, mainstream media did a shitjob of covering these stories).

I have been recommending Meg Ellison’s The Book of the Unnamed Midwife to everyone I talk to: it’s a brilliant post-apocalyptic dystopian evocation of the fundamental importance of reproductive rights: and one that speaks directly to current circumstances in the wake of the Zika virus.

I’d imagine the majority of feminist readers [ETA: of my generation!] can identify the Second Wave elements in her work; a very good review of Tepper’s dystopias by The Rejectionist can be found at Tor.com [now Reactor].

ETA: This section connects to how Joanna Russ’s work influenced me: her book, How to Suppress Women’s Writing, inspired me to develop a five-year plan of reading nothing but women’s writing (after I left academia), and, well, I didn’t stop after five years (there was so much left to read) although I expanded the list to include women writers of color, non-binary and trans* readers (lesbian and bisexual women authors were there from the start!).

Achieved by not ever acknowledging they were “science fiction” or had any relationship to it! Given the dominance of feminist utopias in the feminist sf canon, it’s not surprising the more articles have been written on The Gate to Women’s Country than on Tepper’s other novels. When I checked the Modern Languages Association International Bibliography [in late 2016-early 2017] I found 23 articles or book chapters listed: not all of them are peer-reviewed because the MLA currently includes popular criticism (such as reviews from the New York Review of Science Fiction) and dissertations. Nine of the articles are on Gate; six of those focus on the topic of feminist utopias. Beauty is the second most popular (three articles), and there are single articles on Raising the Stones and Six Moon Dance. I’m the only one [when I wrote this essay!] who has written on her earlier novels, or the trilogies.

My favorite stand-alone novels are Gibbon’s Decline and Fall, The Family Tree, The Fresco and, in other genres, her horror duology about Mahlia and Roger Ettison. I enjoy her two mystery series, published under the open pseudonyms of Orde and Oliphant, but they do not do the kind of work her sf does. Sheri Tepper’s Books.

“Momutes”: Momentary Utopias in Tepper’s Trilogies.” The Utopian Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Twentieth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts. Edited by Martha Bartter, Praeger, 2004, pp. 101-108.

Thesis paragraph: First, to explain the origins of my invented word, “momutes.” In Marianne, The Madame and The Momentary Gods, Tepper’s second novel of the Marianne trilogy, Tepper introduces creatures/creations called momentary gods, or “momegs.” Momegs are “basically a wave form with particular aspects,” beings who “give material space its reality by giving time its duration” (53-4). An infinite number of momegs exist, each with its own locus, and the momegs describe themselves as both a wave and a particle. I argue that Tepper’s trilogies are feminist science fiction and include “momutes,” or momentary visions of utopian possibilities. However, a reading of the trilogies in order of publication reveals that the momutes change over the course of the novels and that the changes in the nature of these momutes correlates with the development of a more complicated narrative structure and with a decreasing trust in human beings’ ability to create feminist/utopian societies. The correlation between the nature of the momutes and narrative structures reveal a change in emphasis from Tepper’s focus (perhaps also reflecting differences in feminist theory) upon the feminist empowerment of an individual woman within a patriarchal and oppressive culture, to the problem of how cultural change on a larger level occur. Cultures are rarely if ever changed by the actions of single individuals who call for such change. Instead, systemic changes beyond the agency of any single individual, involving demographics, technology, and economics, are what lead to cultural changes. Considering the change in culture, the subject of feminist utopias, is a more complex task than the changes in a single individual.

The Plague of Angels trilogy, completed in 2014 with Tepper’s last published work, Fish Tails, crosses over into the True Game World. As a fan of the earlier trilogies, I enjoyed this attempt which I consider equal to, if not superior to, the similar attempts by Robert A. Heinlein and Isaac Asimov to link up all their earlier works as well. [ETA: There are differences between Tepper’s trilogies—clearly plotted out, written and published in sequence—and her looser series which do not follow a single protagonist/plot line in the same way—something I’d be interested in writing about sometime!]

Octavia Butler explores similar themes, notably in the Xenogenesis series in which the Oankali ‘diagnose’ human’s flaws as our intelligence and hierarchical natures and begin a breeding program, and in her Patternmaster series, from a very different perspective and with different results. The difference in their respective handling of this idea—and I think it’s a very important one—is that Butler complicates/explores the negative results of such attempts while Tepper does not (though I think there are some attempts at such complication in her later work).

James Davis Nicoll noted Tepper’s tendency towards eugenics in one of his reviews, and Wendy Gay Pearson wrote an excellent critical analysis in “After the (Homo)sexual: Queer Readings of Anti-Sexuality in Sheri S. Tepper’s The Gate to Women’s Country,” Science Fiction Studies, vol. 23, iss. 2, 1991. The Abstract for Pearson’s essay is here; I am not able to find a version online, though SFS used to have it available. A copy is available in Project MUSE (if your university or library has a subscription), and also at JSTOR (which allows people to sign up for free and get an account that lets them read a certain number of articles online for free).

ETA: Eduardo Bonilla-Silva’s work on unconscious/aversive racism in the U.S. notes the shift in rhetoric to “bad culture” rather than “bad genes,” but it’s a different iteration of racism. His work, and that of other sociologists, focus on the extent to which racism is systemic (and just be understood that way, not just bad behavior/feelings on the part of individuals).

ETA: I have pointed out to a few reviewer that Tepper was in her 80s when publishing the latest books in that series, and if they’re weaker than her earlier work (which she began writing and publishing in her fifties!), well, I suspect that’s not an atypical pattern for writers!