I joined LiveJournal through the encouragement of two friends I met at the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts in 2003: they were both active in fandom, especially the transformative works (fanfiction) parts of fandom, and we were all Major Fans of the Jackson films. I remember telling them at the banquet that I would use the invitation code one would send me to join, but it was just to keep up with what they were doing. I was NOT going to write fanfiction! Heavens, no.

On the plane ride home (from Florida to Texas), I started writing my first Real People Slash (RPS) story, focusing on David Wenham and Elijah Wood (Faramir and Frodo), and well, as another friend would later tell me, anytime she saw/heard me say I would not ever do X, she could pretty much count on a story all about X showing up in my LiveJournal fairly soon.

I'd been active in what I'd call "con" fandom (belong to a Star trek fan club in college, attending sf cons in the Seattle and Portland areas) during the late 1970s/early 1980s. I then became active in Amateur Press Association (APA), creating fanzines for a group collated fanzine every month, from the middle 1980s to the early 1990s when I GAFIATED from fandom (for good) as I thought once I began writing my dissertation.

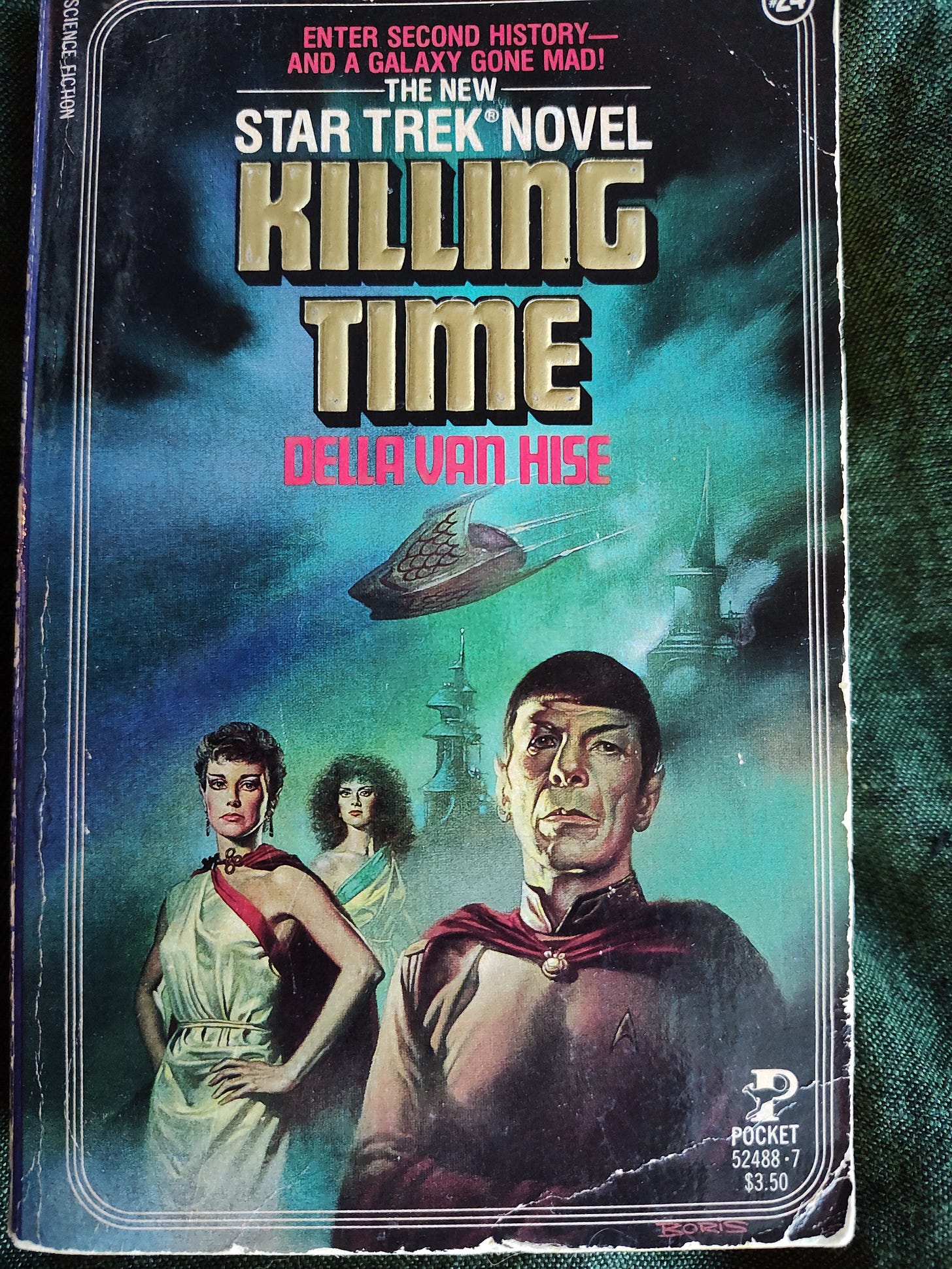

During all those years in fandom, I never heard a whisper about slash. Of course, in both areas of fandom, the spaces I was in were almost entirely inhabited by straight white men (not uncommon at the time). I learned about slash fiction from academic presentations and publications given during the 1990s at the Popular Culture/ American Association conference, presentations by two Canadian women1 who were collaborating on work about how some of the writers of Trek slash fiction managed to import some of the slash conventions into some of the earliest Paramount tie-in novels (and what happened when the Powers That Be realized it: Della Van Hise, Killing Time

I own a copy of the first, recalled edition, snicker, and have shared a picture of it below! Note that the cover foregrounds Sexy Spock and two Sexy Ladeez! (none of whom look like they are in a typical SF/ST novel!)! No sign of Ensign Kirk (yes, the alternate time story involves Captain Spock/Ensign Kirk!). I still vividly remember the first time I read the Famous (or according to Paramount, INfamous) scene on the holodeck with Captain Spock physically pinning Ensign Kirk. That scene was pure slash (though nothing actually specifically sexual happened). I knew, somehow that this was NOT your typical Trek novel (though I didn’t know *what* it was then).

So I was fascinated by the presentation at PCA and started looking for more scholarship on slash fiction. Then, after I became involved in fandom, and was writing slash fiction, and reading liek WHOA!, it all led to a 2009 essay, "Thrusts in the Dark: Slashers' Queer Practices,” which was published in Extrapolation.2

What follow is a chunk that was part of the original draft of the essay which began to analyze a survey I did of reading preferences (fanfic and original fic) of the fans of two dark FPS stories that were well known, popular, and controversial, among some parts of LotR fandom. The editor of the journal asked me to cut that section out, perhaps to develop into another essay (well, he more or less said, "you have two if not three essays in this piece," listed them, and told me that if I developed one and resubmitted, he'd probably publish it). I picked the easiest one to keep, cut the rest, resubmitted, and he published it. But I never got around to developing the part I cut out which makes it a great candidate for sharing here on my new Substack!

I suspect my tables are really badly formatted for reading; I’m new to Substack, and will be trying to find some resources to read to improve table formatting for posting here since I have a number of bits and pieces with numerical data from my corpus stylistics Tolkien project.

Keep in mind this piece was written in 2008 more or less, and I haven't updated/revised it with later scholarship on the question of pornography and fanfiction which does exist! I have lightly edited the piece to correct errors or clarify language on the sentence level, and have added a few sentences that refer to the published essay from which this excerpt was taken.

The Unpublished Survey Results

Note: five of the first eight paragraphs are very similar to paragraphs in the published essay, but I think my use of them here, fourteen years after the original journal publication, and in a completely different context, and followed by material which was never published falls under fair use!

Joanna Russ is one of the earliest feminist writers to discuss slash in the context of the 1980s feminist sex wars and to argue for the connections between slash and pornography. In her essay, "Pornography By Women For Women, With Love," she starts by asserting "Yes, there is pornography written 100% by women for a 100% female readership" (79). Camille Bacon-Smith describes the conflicts in fandom over Russ' essay. She published two versions of it, one in a fanzine written for fans as a fan, and the other as an academic for academics which contained more academic discourse. But her use of "pornography" was controversial at the time (and remains so).3

I read the essay in her 1985 collection of essays, Magic Mommas, Trembling Sisters, Puritans and Perverts: Feminist Essays [highly, HIGHLY recommended].4

Russ brings a perspective other academic scholars of slash do not always have: she is a feminist theorist as well as one of the major writers of 1970s feminist sf. Other essays in Magic Mommas deal with questions of conflict and power in the feminist movement, including the 1980's sex wars. She argues in "Pornography and the Doubleness of Sex for Women," that "[t]he only people capable of analyzing what fantasies really mean are those to whom the fantasies appeal most." She appends a note to her text after that statement: "This doesn't mean that they will analyze them, or that their analyses will be accurate; it means only that they can know the context of such fantasies" (111).

In the essay, she is discussing sexual fantasies, sexual behaviors, rape culture, and feminist debates over pornography, including whether what women produce can ever be called pornography. Scholars seem happy with claiming that romance serves the same function for women as pornography serves for men, but that leaves the question of what texts that are emphatically not "romances" and might with some justice be called "pornographic" fit into the categories.

Debates over the terms romance, erotica, and pornography continue within fandom, with some fans claiming "porn" as a term for celebrating and praising their favorite slash and others rejecting it as a term limited to commercially produced material that exploits women solely for men's pleasure.

The majority of scholarship on slash (when I wrote this essay fifteen years ago!) tends to claim romance elements over pornographic elements; only Catherine Driscoll, in "One True Pairing: The Romance of Pornography and the Pornography of Romance" (Hellekson and Busse), builds on Russ's work, arguing that, instead of considering "romance" for women and "pornography” for men as separate genres, understanding that fanfiction draws upon both genres and yet fits neither's conventions fully, and considering the shared cultural and literary ancestry of the two genres in the western literary and popular culture.

At this point, I am not willing to argue where sexually explicit fan fiction and pornography do or do not intersect. Sexually explicit stories, especially slash featuring male/male pairings, has been the focus of more academic scholarship than the other genres perhaps because of the perceived oddity of "straight women writing queer men," a definition which is still presented with breathtaking innocence and confusion in mainstream media.5

The stories I analyze in "Thrusts in the Dark: Slashers' Queer Practices" (2009) include explicit narratives of sex and kinks (in one case, incest, and in the other, whipping and BDSM) and would probably be described by many of their fans as erotic, undoubtedly by some as pornographic (as a negative judgement).6 The authors draw on discourses of sexuality that are controversial in mainstream North American culture, in some feminist cultures, particularly Second Wave American feminism, and in some fandom cultures. However, it is important to emphasize the extent to which fans of both of these stories, including myself, also take pleasure in the depth of characterization, exploration of character psychology, the complexities of plot, and the other literary elements, including the felicities of the authors' writing styles.

Because of the intense interactions between readers and writers in fandom, I decided to investigate reading and viewing preferences of the fans of the stories, including their preferences in original fiction and media texts, not just fan fiction. I hypothesized that readers who identified as fans of these stories might also choose to read and view texts in genres not traditionally associated with traditional feminine pleasures.

I designed a questionnaire which was approved by my university's Institutional Review Board and posted on a LiveJournal site, dr_robin_reid. The survey was online for three months. I asked the two authors to post a link to the survey on their journals and at the various fan sites where the two stories were archived.

The questionnaire asked basic (and open-ended) demographic questions and asked readers to choose from a list of genre preferences both inside and outside fandom. Respondents could choose as many of the genres listed as they liked, and could identify other genres in screened comments. Respondents did not have to and in fact did not provide answers to all the demographic information; in other categories, they were not required to indicate preferences in any way.

Since I had no training or experience in crafting surveys, I had tried to find peer-reviewed work that was relevant to my topic, for my review of scholarship, and to use as a model for my questionnaire. I found that academic scholarship on the genre and reading preferences of adult women is difficult to find (if that has changed in the past fifteen years, I’d love to hear about it — feel free to post sources in comments!). Most reading preferences scholarship focuses on children and adolescents.

From what I gathered, boys/young men tend to prefer scary and/or violent stories to romantic stories, while, as is usually the case, girls are more likely to cross gender boundaries although those girls are typically evaluated as aggressive in the language of the scholarship. The development of separate commercial categories of literature in the 19th century, which was reflected in sharply divergent publications for boys and girls, often goes unquestioned today when it seems that many assume the idea of separate genres for the two different normative genders is natural rather than socially constructed outcome.

Evidence for what adult readers and viewers prefer can be found in some marketing publications, but lack of evidence and concern about how stereotypes drive the research make it problematic to draw upon. Much of the marketing scholarship that exists focuses on television rather than other media. When it comes to written texts, there is a general consensus is that genre romances are the best selling category of fiction and science fiction is a fairly small market in comparison, but that consensus simply seems to replicate that most likely element of reading preferences studies without spending time considering what boundary crossing is taking place by women.

The only study I found on adult genre preferences was a 1997 study by Stuart Fischoff, Joe Antonio, and Diane Lewis on film genre preferences. The study covered 560 respondents ranging in age 15-83, having educational levels from high school to graduate degrees, and from a range of ethnic groups (Asian, Black, Latino, Other, White). Respondents were asked to list up their favorite films, up to fifteen; the lists of specific were then sorted into genre categories by the researchers. The study results discuss age and ethnic differences as well as gender, but I did not carry those into my study. I cite the article and its original URL in my “Works Cited,” but when I checked, I found that it was no longer available. I found a 2017 article that cited it that might be worth reading (Wühr, Lange, and Schwarz, citation in footnote 9).

Fischoff, et. al identify the most popular film genres chosen by men as: Drama (30.2%), Action Adventure (20.2%), with Comedy and Science Fiction/Fantasy tied (10.6 and 10.7 %) in third place. In contrast, the most popular genres among women are: Drama (31.2%), Romance (15%) and Action Adventure (12.5%).

Women as a group are shown as having a higher tolerance for male-oriented films than men do for romance, but I note the difference between women's preference for Action Adventure (12.5%) and men's preference for romance (9.6%) is a small one.

I lack statistical training, but this difference leads me to wonder if women's preference (or lack of) for "masculine" texts is always that markedly different than men's preference (or lack of) for "feminine" texts. For whatever reason, the data clearly shows minority populations within each group who may cross stereotypical gender/genre preferences: 9.6% of the men chose Romance although only 4.6% of the women chose Science Fiction/Fantasy.

Fischoff, et. al.'s data supports the general sense of a connection between gender and genre preferences but provides statistical data showing the presence of a small group in every demographic category, as do other studies on genre/gender reading preferences. For that reason, and the reason that the range of genre terminology generated by his study could be used with some modification for my study, I chose his work as the primary model for my gender/genre preferences terminology although I made some small modifications.

The major difference in terminology was that Fischoff's study focused on mainstream film categories, they did not collect information on preferences for erotica and pornography. I was not too concerned that the study focused solely on films since my knowledge of fans confirms that many of us are active readers and active consumers of a variety of media.

I collected data from volunteers who knew and liked the two stories, specifically demographic information and genre preferences. My hypothesis—that the genre preferences of the readers of these two stories might be different than many women's was supported—the resulting data (a very small N that I know is not in the least sufficient to make any statistical argument) shows that the preferences of the women in my group do not correlate to the women in Fischoff study nor, arguably, to standard gender/genre preferences.

Twenty-seven fans took my survey, ranging in age from 18-59. All but two identified as female; those two did not specify a gender, only a sexual identity (heterosexual and bisexual). Nine respondents identified as straight; three as bisexual; two as lesbian. Thirteen did not choose to provide information on sexual identity.

In terms of nationality, seventeen identified themselves as U.S. citizens; three as English; one as French; one Italian, and one Indonesian. Obviously, my small group of fans skews high toward liking science fiction and fantasy since we are all in Lord of the Rings fandom, so we probably are closer to that 4.6% minority of women in Fischoff's study who enjoy that genre. My preliminary observations on the data shows that the group tends not to prefer only genres defined as traditionally masculine or traditionally feminine either in our popular reading and film viewing or in our fan fiction reading.

For example 52% of my respondents chose Action as one of their favorites genres (compared to 20.2% of males and 12.5% of females in Fischoff), and 78% chose Science Fiction (compared to 10.7% and 4.6% in Fischoff). Romance was chosen by 26% of my respondents (compared to 9.6% of males and 15% of females in Fischoff).

While I was asking for genre preferences rather than titles of individual films, allowing much more leeway, I suspect that my results, even with the extremely limited numbers, may reflect a tendency among fans to be, as I noted above, major consumers of texts, both literary and graphic. That is, the differences could be explained by the differences between a more randomly chosen "mainstream" group of respondents and self-chosen members of fandom.

Table 1 Genre Preferences Reid Books and Film and Television & Fischoff et. al. Study

Many Lord of the Rings fans tend to group in specific sub-communities. One of the main divisions involved the races (or species!) of characters: Hobbit fans/Hobbit fics, Elf fans/Elf fics (often heavily influenced by The Silmarillion), and Men fans/Men fics (although many fans read in all three areas).7 There tends also to be an assumption that many fans read selectively in specific genres.

My data tends to work against that assumption with regard to this group. When asked what genres of fics they preferred reading in fandom, the readers who identified as reading Het and/or Domestic fic also identified Slash as a genre they read. Only four of the twenty-seven respondents indicated they read only het and none of the other three main genres.

Just as they tended to enjoy masculine-identified genres, such as pornography, science fiction, sports, and thrillers, the women in my group prefer those genres of fic which are more controversial: 77% enjoying dark fics, 52% PWP (plot, what plot, or porn without plot), and 41% enjoying rapefics.

Table 2 Reid Study LOTR Fan Fiction Genre Preferences

I was rather surprised to see the strong differences between all but one of the genre preferences (the one exception being the Plot-What-Plot (PWP) category) in Fictional People Fiction/Slash (FPF/S) and Real People Fiction/Slash (RPF/S). Since Real People Fiction creates stories based on actors and other celebrities (musicians, sports figures, pundits, politicians), it seems likely that some fans cannot take the same pleasure in some of the darker and more graphic story elements when the story features fictional characters based on "real people."

This limited study raises a number of questions for further work, especially in the areas of reading and writing practices, within fandom, and perhaps without.8 Most scholarship on reading preferences that I looked at constructs readers as more or less passive consumers of work produced by others whereas, in fandom, many (not all) readers are also writers, and the members of communities are often engaged in a variety of other interactions (discussions in personal and community journals; writing challenges; writing meta, or analytical essays on the source texts and on fandom; offline interactions including conventions and personal visits). (One question is whether or not that assumption of the scholars doing the reading preferences scholarship is in any way accurate!)

The question of fandom reading and writing practices and queer reading and writing practices, and where those overlap and where they diverge, is also worth pursuing in future work. Queerness need not be limited only to darkfics, but I would like to see more work done with these fics in future as well. Vids, usually considered separately from fics, might instead be paired with fics in the same fandoms, with analysis of dark elements in both written and graphic forms.

The possibilities for future scholarship are limited only by the internet!

(And time. And energy! And everything that kept me from developing this into a full essay all those years ago!)

Works Cited

Bacon-Smith, Camille. Enterprising Women: Television Fandom and the Creation of Popular Myth. U of Pennsylvania P, 1992.

Driscoll, Catherine. "One True Pairing: The Romance of Pornography and the Pornography of Romance." Fan Fiction and Fan Communities in the Age of the Internet. Eds. Kristina Busse and Karen Hellekson. McFarland, 2006. 79-95

Antonio, Joe, Stuart Fischoff, and Diane Lewis. "Favorite Films and Film Genres As A Function of Race, Age and Gender." 1998. NOTE: The original link I provided (http://web.calstatela.edu/faculty/sfischo/media3.html) no longer exists.9

Lamb, Patricia Frazer, and Diane Veith. "Romantic Myth, Transcendence, and Star Trek Zines." Erotic Universe: Sexuality and Fantastic Literature. Ed. Donald Palumbo. Greenwood P, 1986. 236-55.

Reid, Robin Anne. "Thrusts in the Dark: Slashers' Queer Practices." Extrapolation, vol. 50, no. 3, 2009, pp. 463–83. https://doi.org/10.3828/extr.2009.50.3.6.

Russ, Joanna. "Pornography by Women, for Women, with Love." Magic Mommas, Trembling Sisters, Puritans and Perverts: Feminist Essays. The Crossing P, 1985. 79-99.

I cannot remember their names, and they did not return to the conference in last years. As far as I know, alas, they did not publish anything. I did manage to exchange emails with one of them a few years later, and remember her telling me that they eventually found writing slash fiction more fun than writing scholarship about it and had not published. I can understand that reason: I found writing slash fiction (and READING it) in LotR fandom immensely satisfying although I also love to read and write scholarship about fanfiction, and fandom, as well as Tolkien. However, I still remember my first faculty developmental leave in 2004 [no sabbaticals allowed in Texas] when I was trying to write an essay on queer theory and vampire fiction by women and found myself suddenly writing a queer vampire/pirates slash fiction suddenly ending up writing 60,000 words of a novel that featured the LotR actors. I still hope to get that together enough to publish someday (with the names and fannish-specific details changed or removed!).

Oddly enough when I was Googling around to see if “Thrusts” was available online, I found that somebody had made it into an e-book and had tried to sell it on Amazon although, at the moment, it’s not available. But it has my name on it although I didn't post it, and if it sold any copies, I never got any payment.

In contrast to Joanna Russ' focus on slash fiction as pornography, the other early essay on slash fiction by Patricia Frazier Lamb and Diane Veith focused on slash as romance fiction. Russ cites Lamb and Veith’s ovular essay. I would say that slash can and does contain multitudes of genres, so there's no point in arguing whether the Big P or the Big R genre is more important or dominant, and I like work in both genres (and a wide spectrum in between) in both fan- and original fic!

All of Joanna Russ’ work is highly recommended (though of course I have my favorites). I consider her as one of the two writers whose work most influenced me as a person and a writer and a feminist. The other is Tolkien. I know, some of my friends are weirded out by this fact, and the fact that I went from ten years doing scholarship on feminist speculative fiction to doing scholarship on Tolkien. I’ve been trying to tackle the Russ and Tolkien love for years, and am hoping to be able to publish something before I die.

I’m fairly sure that the astonished stereotype has mostly disappeared as of 2023, but I would not bet against it still existing in some places. But I haven’t really tried to track how the media handles fan fiction (or transformative works) these days because so much has changed in recent years. But remember this piece was written in 2008!

Here are the two excerpts from the stories I placed at the start of my published essay:

Boromir was breathing hard. "Once," he gasped out "Once, I swore I would never touch you again. I wanted to save you, and Denethor had reminded me to be worthy of Gondor. Now. . .I do not care if am forsworn. I do not care if we are cursed or Gondor is cursed or the world is cursed." He rubbed his thumb over Faramir's swollen lips. "But if I must pay with my soul, I will have what I paid for."

He rose up over Faramir. His hands settled on Faramir's thighs and pushed his legs open. He looked an elbow under Faramir's knee and lifted him up. "In full measure, sweet brother." ("The House of Hurin" by Kirby Crow Part IV).

Fifteen more times Merry brought the whip down upon Frodo's bleeding, battered back, criss-crossing it with angry lines that wept blood. He was in such deep and pure agony that he very nearly passed out. He bucked and screamed and cried, but nothing he did seemed to make the misery end….But bad as the burning was, as bad as the sharp sting of the leather on his skin, the pain in his heart was tenfold. He had tried to believe that Merry could be saved. Had willed himself into trusting that there was some small part of his cousin left in the body that strode about in his skin and spoke with his voice. He was a prisoner and at present it seemed his jailor would either break him or kill him. (Ring Around the Merry by Aelfgifu, page 106.)

There are of course many other differences and groupings, but in this case the two Alternate Universe Fics I chose were from the Man and the Hobbit groups, with Boromir/Faramir the main characters in one and Merry/Frodo (the major characters in the other although Pippin and Sam were also important).

Dawn Felagund, founder of the Silmarillion Writers Guild (SWG), who publishes under Dawn Walls-Thumma as well, is doing amazing work with two surveys (one done with Maria Alberto) on Lord of the Rings fandom. Some of the results can be found in posts in the SWG’s Cultus Dispatches. HIGHLY recommended!

While searching for another version of the Fischoff, et. al. study online, I found this 2017 article that cites it and that seems to be something that would have been very useful back in 2008!

Wühr, Peter, Benjamin P. Lange, and Sascha Schwarz. "Tears or Fears? Comparing Gender Stereotypes about Movie Preferences to Actual Preferences." Frontiers in Psychology, March 2017. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00428.

I downloaded a copy and plan to read it which might result in a later post!