The Relative Strengths of Lewis and Tolkien Scholarship

Part 3: BUGBEARS Destroying Literature Culture & CIVILIZATION Since . . . . .FOREVER!

FYI: I should warn you all that this post is way long (the program has been telling me “too long for email” during all my recent revision sessions). I have some strong feels about Bugbears . . . .

Sound Cue: Imagine the dramatic pounding theme music that heralds the entrance of The Monsters in sword & sorcery/action/horror movies playing as you read Part 3!

Join the Bugbears!1

This post is the third of a four-part series responding to a Lewis scholar’s, Brenton Dickieson’s, exploration of his question about why Tolkien scholarship is stronger than Lewis scholarship. My concluding post will discuss how this attempted interaction is similar to two others that I have written about recently (one in this Newsletter, in Decorum vs. Diversity, and the other in Mythlore2 ).

In Part 1, the Introduction, I give some background on why I wrote the original response to Dickieson's series, and in Part 2, “A Summary and Some Niggles,” I summarize his overall argument in his first two posts, the reasons he gives to support his self-described "fighting words thesis," and explain my niggles with some of his claims.

I call these “niggles” because I am largely in agreement with Dickieson's main point and enjoyed reading the series. He is a good writer and engaged with a number of critical/cultural concerns that are of interest to me. I found Dickieson’s third and final essay, Other Factors to be the most interesting as well as the part that I most wanted to engage with.

Even now, I would like to talk with Dickieson more about his experiences with and ideas about theory and Lewis, and my ideas about theory and Tolkien, and probably, most of all, our ideas about “theory” (and what it means to us).3

In his Part 3, Dickieson argues that some of external factors relating to developing scholarship on Lewis and Tolkien differ enough to have resulted in stronger scholarship in Tolkien studies. These "other factors" include the biographical and archival tools produced for both writers by their respective literary executors (Christopher Tolkien vs. Walter Hooper); the extent to which some Tolkien scholars are open to working with what Dickieson calls the "bugbear of literary theory"; the different “Literary Societies” for Tolkien vs. those for Lewis; and, finally, the extent to which how Lewis scholars, who value their “Christian fellowship” and its emphasis on friendship over critique of published scholarly work, has affected the quality of scholarship.4

My focus here is the “Bugbear of Literary Theory.” Those who know that I am a queer feminist atheist autist whose doctoral work and scholarship is primarily All About The BUGBEARS5 will probably not be surprised that Dickieson’s metaphor got my attention.

People who know me or my work might be surprised that the first two things I did was an image search followed by looking up the word in the Oxford English Dictionary.6 I resisted the impulse to make a list of All the Things that have been compared to/described as a bugbear — at least for the moment.7 No promises about later. If I had done that, this post probably would have become at least two posts which I thought possible at some point.

Aside: It would be fun to make a table that shows the literal vs. metaphorical uses of the word (and Substack can apparently handle table formatting, so I really need to learn how to do that).

Ahem.

Behold the BUGBEAR!

Image source: From Wargamer Mara Franzen

Although I have been a Tolkien fan for fifty-seven years, I have never been a D&D or any RPG player. The world of the games always seemed vastly inferior to Tolkien’s creation. I did not know that Bugbears are a playable monster in D&D. I now like the idea of playing an Academic Bugbear in real life, so I snicked the metaphor and expanded it.

More seriously, I question how good a metaphor “bugbear” is for the controversial issue of “literary [critical] theory,” probably in my conclusion, Part 4, where I might sneak back to the possibility of the Bugbear list to discuss the difference between the lexicographical meanings of the words and how the OED selected quotes illustrate the ways writers used it in its native habitat, so to speak.

Oxford English Dictionary Entry “Bugbear”

I bolded the definitions so they would stand out amongst the illustrating quotations.

Bugbear, noun

Forms: 1500s buggebear, 1500s buggebere, 1500s–1600s bugbare, 1500s–1600s bugbeare, 1500s–1600s buggebeare, 1500s– bugbear, 1600s buckbear, 1600s bugebear, 1600s buggbear, 1900s– bugabear.

Frequency (in current use): This word belongs in Frequency Band 4. Band 4 contains words which occur between 0.1 and 1.0 times per million words in typical modern English usage. Such words are marked by much greater specificity and a wider range of register, regionality, and subject domain than those found in bands 8-5. However, most words remain recognizable to English-speakers, and are likely be used unproblematically in fiction or journalism. Examples include overhang, life support, register, rewrite, nutshell, candlestick, rodeo, embouchure, insectivore (nouns)...

Origin: Apparently formed within English, by compounding. Etymons: bug n.1, bear n.1

Etymology: Apparently < bug n.1 + bear n.1

Compare bearbug n. at bear n.1 Compounds 2a, bull-bear n., earlier bogle n., and also bug-boy n., bugaboo n.

The form bugabear appears to show alteration by association with bugaboo n.

In spite of the chronology of the examples, it is likely that sense 2 was the original sense. However, despite the apparent etymology, evidence to suggest that this imaginary being was thought to have taken the form of a bear appears to be lacking.

1. An object or source of (esp. needless) fear or dread; an imaginary terror. Now esp.: a cause of annoyance, anxiety, or irritation; a pet hate.

1552 R. King Funerall Serm. sig. F.iiiiv Momishe mopers whiche can do none other thyng else, but mope vppon ther bookes, to make vs afraied of shadowes and buggeberes.

c1580 tr. Bugbears i. i, in Archiv f. das Studium der Neueren Sprachen (1897) 98 306 In stide of taies, he hathe bugbeares in his head.

a1586 Sir P. Sidney Arcadia (1590) iii. xxvi. sig. Yy6 At the worst it is but a bug-beare.

1642 D. Rogers Naaman To Rdr. sig. Bv All you that thinke originall sinne a bugbeare.

1678 S. Butler Hudibras: Third Pt. iii. 193 Who would believe, what strange Bug-bears Mankind creates it self, of Fears?

1717 W. Kennett Let. in H. Ellis Orig. Lett. Eng. Hist. (1827) 2nd Ser. IV. 306 The king of Sweden is every day a less bugbear to us.

1783 S. Johnson Let. 27 Nov. (1994) IV. 250 Hystericks..are the bug bears of disease of great terrour but little danger.

1841 C. Dickens Old Curiosity Shop i. iii. 86 What have I done to be made a bugbear of?

1871 E. A. Freeman Hist. Norman Conquest (1876) IV. xvii. 51 Confiscation, a word which is so frightful a bugbear to most modern ears.

1880 ‘G. Eliot’ Let. 14 Sept. (1956) VII. 322 Our only bugbear—it is a very little one—is the having to make preliminary arrangements towards settling ourselves in the new house.

1903 H. Keller Story of my Life xx. 71 The examinations are the chief bugbears of my college life.

1966 Eng. Stud. 48 163 We hear far too much of those bugbears, the ‘grammarians’, and their camp-followers, Fowler and Partridge.

2010 Independent 3 Dec. (Viewspaper section) 20/1 It is a bugbear of mine that in swanky hotels..the hall porter insists on commandeering bags that you are perfectly able to carry yourself.

2. An imaginary evil spirit or creature said to devour naughty children; a bogeyman. Now somewhat rare.

?c1570 Buggbears iii. iii, in R. W. Bond Early Plays from Italian (1911) 117 Hob Goblin, Rawhead, & bloudibone the ouglie hagges Bugbeares, & helhoundes, and hecate the nyght mare.

1592 T. Nashe Pierce Penilesse (Brit. Libr. copy) sig. I4 v Meere bugge-beares to scare boyes.

1607 E. Topsell Hist. Foure-footed Beastes 453 Certaine Lamiæ..which like Bug-beares would eat vp crying boies.

1651 T. Hobbes Leviathan i. xii. 55 Ghosts of men deceased, and a whole kingdome of Fayries, and Bugbears.

1758 S. Johnson Idler 24 June 89 To tell children of Bugbears and Goblings.

1840 R. H. Barham Look at Clock in Ingoldsby Legends 1st Ser. 61 The bugbear behind him is after him still.

1953 K. M. Briggs Personnel of Fairyland Gloss. 193 Bodach, the Scottish form of bugbear or bug-a-boo. He comes down the chimney to fetch naughty children.

1998 M. Warner No Go Bogeyman (2000) i. 35 Bugbears are not Death's twins or his messengers,..they resemble Death in matters of appetite and movement.

Bugbear, verb,

Forms: see bugbear n.

Frequency (in current use): This word belongs in Frequency Band 3. Band 3 contains words which occur between 0.01 and 0.1 times per million words in typical modern English usage. These words are not commonly found in general text types like novels and newspapers, but at the same they are not overly opaque or obscure. Nouns include ebullition and merengue, and examples of adjectives are amortizable, prelapsarian, contumacious, agglutinative, quantized, argentiferous...

Origin: Formed within English, by conversion. Etymon: bugbear n.

Etymology: < bugbear n.

Now somewhat rare.

transitive. To fill with (esp. needless) fear or dread; to plague, trouble.

In quot. 1644 with punning reference to terror caused by a bear.

1644 J. Booker No Mercurius Aquaticus 7 Tell Ursa Maior, and Ursa Minor, that..I have appointed him [sc. Endimyon Porter] to be their chief Beare-Ward.., that Mercury the Irishman may passe freely to Iupiters Court, without fear of being Bugg Bear'd by the way.

1650 R. Stapleton tr. F. Strada De Bello Belgico x. 1 They carryed the Warre up and downe, only to bug-beare Townes and Villages [L. oppidulis ac pagis arma circumferre].

1705 S. Whately in W. S. Perry Hist. Coll. Amer. Colonial Church: Virginia (1870) I. 167 To be bugbear'd out of our senses by big words.

1775 Inq. Policy of Laws 75 The People of Ireland were so industriously bugbeared (to use his own Expression) with Fears of the Pretender.

1850 R. Armitage Dr. Johnson: Relig. Life & Death 460 The clergy cry out against such things as are here recommended, as leanings to Popery, so perpetually is Protestantism bugbeared by her own confession of weakness.

1888 ‘Garryowen’ Chron. Early Melbourne II. l. 687 From the evil of the abortive celebration sprang one good result—viz., that no other July anniversary was bug-beared by an Orange procession.

1903 M. Van Vorst in B. Van Vorst & M. Van Vorst Woman who Toils viii. 248 The clock of Excelsior..glared in upon us, giant hands going round, seeming to threaten the hour of dawn and frightening sleep and mocking, bugbearing the short hours which the working-woman might claim for repose.

1975 Times 28 Apr. 13 The same moral pretentiousness and dishonesty that has bugbeared United States policy in Indo-China.

First, I want to acknowledge that, unlike some academics in Tolkien scholarship (and in almost all other fields of literary studies I am familiar with), Dickieson is not attacking The Bugbear theory. In fact, his choice of the word “bugbear” for his metaphor could be read (in the context of the definitions above) as implying that the resistance he sees among Lewis scholars is perhaps needless, or needs to be changed.

By "not attacking," I mean that he does not say, specifically, "[insert critical theory of your choice] is ruining Tolkien scholarship," a statement I have heard at conferences, have seen in Tolkien Facebook discussions, and have seen seen used in online attacks against a number of us who use certain literary/critical theories.8

I realized as I was revising this section that Dickieson's argument reminds me of one of the arguments about "theory" that Michael D. C. Drout and Hilary Wynne make in their otherwise excellent bibliographic essay. Drout pursues that argument with some expansion in a later solo publication.9 That connection is one reason why this post is so long: I realized that I already knew about essays that showed how some Tolkien also scholars resist certain contemporary theories and are not afraid to say so, and I wanted to talk about their arguments, and my niggles with them.

As before, I summarize Dickieson's points, providing some specific quotes, and then respond with my niggles. I then provide some quotes from Drout & Wynne, and Drout, and explain my niggles with those parts of their two otherwise excellent essays (one of which, the bibliographic one, I have cited a number of times).

Dickieson’s Bugbear & My Niggles (Specific & General)

I would summarize his claim about the “Bugbear of Literary Theory” as saying that Tolkien scholarship is more welcoming than Lewis scholarship to some of the critical theories originating in the second part of the 20th century (meaning, after WWII), as opposed the literary theories which originated in the first half of the 20th century (the 1920s saw the development and growth of New Criticism, Marxism by way of The Frankfurt School which was getting its start in the 1920s, as well as Freud’s psychoanalytical theories which were beginning to be applied to literary texts in the United States).

But I realize that I am including more information than Dickieson includes: and perhaps making some assumptions about what he means. He identifies “New Criticism” and psychological theory briefly, as well as praising work done in Tolkien studies using “linguistic and medieval theories” as well as a few other more vaguely specified theories. So I decided to use more quotes than I might otherwise because I am not sure how fair my summary is.

Dickieson opens the Bugbear section, “9. The Bugbear of Literary Theory,” by listing three recent Tolkien publications (all of which I have read) that he thinks exemplifies the different attitude toward theory in Tolkien studies.

In my first post in this series, I invited readers to look at academic book catalogues or award finalists and compare Lewis and Tolkien scholarship. One trend is clear in three important Tolkien books from Palgrave MacMillan:

Dimitra Fimi, Tolkien, Race, and Cultural History: From Fairies to Hobbits (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), Mythopoeic Award winner in Inklings Studies

Jane Chance, Tolkien, Self and Other: “This Queer Creature” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), Mythopoeic Award nominee in Inklings Studies

C. Vaccaro and Y. Kisor, eds, Tolkien and Alterity (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017)

Each of these strong volumes represents theoretical approaches to literary criticism in this generation. There are many great Tolkien volumes that are not driven by literary theory particular to the last century, such as (for the most part) Amy Amendt-Raduege’s 2020 Inklings Studies award-winning volume, “The Sweet and the Bitter”: Death and Dying in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (The Kent State University Press, 2018). However, with exceptional strength in linguistic theory and medieval studies, Tolkien scholarship is often able to walk with literary theory in fruitful ways (emphasis added).

In contrast to Tolkien scholarship, Dickieson goes on to say:

I have discovered a real resistance in many strands of Lewis scholarship to using literary theoretical tools. That there is a broad and energetic conversation about “Queering Tolkien” is telling: there really isn’t anything like that in Lewis studies, though I think Lewis’ fiction invites such a reading. Lewis’ work begs for a discussion on “alterity”–or “the taste for the other” in Lewis’ own words. What can linguistic theory, in-depth political science questions, or speculative world-building scholarship (emphasis added) teach us about Lewis’ fiction? We don’t know–or don’t know fully–because of an anxiety in the field about literary theory (emphasis added).

I think this resistance to lit theory comes from four main points of resistance, I think: 1) following Lewis in resisting certain kinds of reading approaches (like psychological approaches or the conversation in The Personal Heresy that actually helped stimulate the “New Criticism” theory movement); 2) a conservative resistance to identity studies among some Lewis scholars; 3) the elitist nature of the literary theory conversation itself; and 4) theoretical conversations about Lewis’ work that have not always read Lewis well or that aren’t evidentially based.

I bolded phrases that I have specific niggles with and will move from those specific niggles about these phrase to more general niggles, especially relating to the four reasons for the resistance Dickieson gives in the last paragraph quoted above (most if not all of that would have been bolded otherwise!).

Specific Niggles

“in this generation” I am not quite sure what generation Dickieson is talking about, but I am pretty sure that the three authors listed are not members of the same demographically defined generation.10 Perhaps Dickieson means the "generation of the scholarship," but I would need more information to evaluate that claim (and an explanation of how one defines a "generation" of theory/scholarship").

I consider Jane Chance to be one of the three founding members of Tolkien studies as an academic field (I define a 'founding member' as someone who changed the disdain and dismissal of Tolkien scholarship by literature departments by their publications, editing, and conference activities). I consider the with the other two founders being Verlyn Flieger and Tom Shippey.11 They are all retired (though still active!). Each has had collections of essays by others in the field published in their honor.

In contrast, Dimitra, Chris, and Yvette are all younger than Jane (and younger than me—I just retired in 2020). All three are are well-established scholars with significant and multiple publications. I have known them all almost two decades; I gave my first presentation at the Kalamazoo Medieval Congress in 2004, and I met them all at that conference). They are certainly not the "newest" of “youngest” generation of Tolkien scholars which I would define as graduate students and recently graduated doctoral students and early career scholars (often job searching or, at best, newly hired — and not necessarily in tenured positions). If I had to come up with a generational type of category, I would say they are mid-career scholars.

Nor do the three books reflect a single “generation” of theory in any sense I can discern. The three books were published between 2009 (Fimi), and 2016-2017 (Chance; Vaccaro and Kisor). The first is a cultural or intellectual history that traces the influences on Tolkien’s thinking about his “races” (species) and how that changed over his lifetime (as, for instance, the scientific racism of the 19th century was challenged by the scientific theories of the 20th century [Fimi, Chapter 9]) and about how it changed as he moved from the mythic and poetic style and modes of his early years to a novel (The Lord of the Rings). There is, of course, much more to Fimi’s book than I can convey here; I have taught it, and recommend it, and in fact have been known to nag people to read it.

The two later books are both on Tolkien’s “queerness” in the general sense of “alterity” (Chance), and on the range of alterities in his work (Vaccaro and Kisor). Although both books fall under the big umbrella of “alterity,” they have significant differences beyond one being a monograph by a medievalist and the other being a collection of essays by multiple writers (not all of them medievalists).

Chance focuses on Tolkien’s queerness (in the sense of the “abject,” in which queer = “non-normative”), meaning Tolkien’s shyness, his religion, his birth in South Africa, his status as an orphan, his love of inventing languages, and his medievalism, but never sexuality. Her focus is his queer medieval aesthetic in his work; she draws on the work of Tison Pugh, who seems to be the major founder of Queer Medieval Theory (he never wrote about Tolkien), and other queer theorists. Chance describes Tolkien’s values as those of “feminism and humanism” (p. xi). Her book is by a medievalist, looking at how Tolkien’s medieval scholarship intertwines with his fiction, through the lens of difference.

Vaccaro and Kisor’s anthology contains thirteen chapters (the Introduction and twelve essays): the chapters include two bibliographical essays (“Queer Tolkien” and “Race in Tolkien Studies”); two essays on “Women and the Feminine”; three essays on “The Queer” (all different definitions of queerness12); two on language and alterity, and two on “Identities.” A number of the contributors are medievalists but later period and topic specialists are also present. Disclaimer: I wrote the bibliographic essay on “Race and Tolkien.”

literary theory does not have a driver’s license: Dickieson mentions a fourth book, “Amy Amendt-Raduege’s 2020 Inklings Studies award-winning volume, “The Sweet and the Bitter”: Death and Dying in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (The Kent State University Press, 2018)” as a great book (one of many in Tolkien studies) “that are not driven by literary theory particular to the last century” (that is, the 20th century).

I completely agree with Dickieson about the brilliance and quality of Amy’s book (I have known her for years, and we now live in the same town! and get coffee together once in a while. It’s great!).

I completely disagree with Dickieson that her book is not “driven by literary theory” (although, another subjective metaphor sneaks in here with “driven” which, depending on context, could be a positive, neutral, or negative evaluation). I’m also not sure, as I note above what means by “literary theory particular to the last century.”

Here is a short overview on 20th century literary theory from Britannica; here is a more academic/detailed version by Vince Brewton at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Disclaimer: I was one of the peer reviewers for Amy’s book and enthusiastically recommended publication. It deserved the Mythopoeic award. It is on my list of “recommend to everybody to read NOW.”

As someone trained in literary/critical theories of the 20th century, who then went on to teach those theories on both the undergraduate and graduate levels, I disagree that she did not use literary theory. Amy's moving and superb analysis of death and dying in The Lord of the Rings is informed by several major 20th century critical theories that I am familiar with (and often engage in myself right out in public, like all Out & Proud Bugbears), specifically, reception theory (drawing on what readers of the novel have said about it, and how they use it to make meaning in their lives, especially in the moving section at the start about soldiers in Iraq and in the final chapter on "Applicability") and cultural studies (situating her analysis in the historical-cultural contexts of both the medieval texts Tolkien studied and in the present-day context of Tolkien's readers whose ideas about death, she argues, are connected to the medieval ones). Amy is one of many medievalists who does not dismiss 20th century theories! They do exist!! I hang out with them!!!

She also does detailed and strong close readings/explications of parts of the novel (characters who die good deaths, those who die bad deaths, how different cultures memorialize their dead, and those who do not die). That is, she uses another method from another 20th century critical theory, New Criticism. While New Criticism has lost its dominance as being the ONLY theory (when I was taught it during the 1970s, it was never called “New Criticism” or identified as a theory: it was simply presented as “how we analyze literature” by my professors), I think that close reading/explication as a methodology is used by many of us using Bugbear critical theories even if our interpretive goals/purposes have changed (ditto our ideas about aesthetics, and on the need for other types of evidence than the strictly formalist kind).

I suspect one reason a (hypothetical!) reader might consider Amy's book "not-theory" is its clarity of style and accessibility. The stereotype of "theory" is that it is jargon-ridden and confusing (and there are certainly many instances of academic publications that are just that: remember Sturgeon’s law ). But I see no automatic connection between how a work is written (beautifully, boringly, or badly) and its theory.

However, with exceptional strength in linguistic theory and medieval studies, Tolkien scholarship is often able to walk with literary theory in fruitful ways.

I guess Dickieson thinks that Tolkien scholars are open to two types of theory although I would not call linguistics a theory, but is a discipline, and although there are many different linguistic theories, and I’m not sure what one he thinks Tolkien scholars are doing. “Medieval studies” is a multi-disciplinary period specialization (not just literary studies or history but also archeology, languages, material culture and dozens more!) and, as I have already noted, some medievalists are happy to welcome Bugbears into their midst!13 So I’m still not very clear on the theory that Dickieson sees in Tolkien studies.

There have been many changes in linguistics as a discipline since Tolkien’s time, shifting from the major focus on philology (Tolkien's field) which is now called “Historical Linguistics,” to “the scientific study of language.” I taught in a department of Literature and Languages (we had programs in English, Composition, Spanish, and Linguistics).

It is possible to use theories and methods developed in linguistics for literary studies, and I have done so. Some linguistics in recent years have started applying their theories to literary texts as well, including one of my doctoral professors, Michael Toolan. I learned stylistics and applied linguistics with Michael, and I’ve dabbled in corpus literary studies as well.

Roger Fowler was the major founder of the movement to apply theories developed by and for linguistics to literature. I have used M. A. K. Halliday's functional grammar to analyze Tolkien's style of writing as has Michael D. C. Drout who also branched out into digital humanities by creating Lexos in a collaborative multi-disciplinary effort with N. E. H. Digital Humanities funding. This program was created to produce statistical analysis of digitized texts (whether Old English--Drout's main area of interest--or modern English, such as Tolkien used). The list of publications produced by his team gives a sense of the scope and possibilities of Lexos. But there are also the “Tolkien linguists” who study Tolkien’s invented languages — their work/approaches is very different from what those of us in applied linguistics do.

I have blended a Halliday grammatical analysis with queer theory in some of my work. Besides the Tolkien linguists, who study Tolkien's created languages as languages, I do not see much applied linguistics in Tolkien studies. I think one reason is that it's hard to learn linguistics well enough to use it in stylistic analysis; plus, the shift to digital methods requires funding and support which is why most of the really interesting work in this area is being done in Europe, like the recent book, Tolkien as a Literary Artist.

My position is: every single article or book written about Tolkien is working from a theory (some well, some badly) because, at the heart of things, if we strip off some of the admittedly elitist/academic framing of theory (which yes, does exist), all the word in the context of “literary theory” means is a system for determining what is "worth" writing about and how to write about it (purpose and types of evidence). The whole academic discipline of “English” or “Literature” is based on a theory — including what is to be considered “Literature” vs. all those lesser categories (I used to ask my first-year students what their definition of “Literature” was, and they mostly agreed it was the stuff that is assigned in high school that nobody likes and nobody reads, and I was yeah, well, that’s not wrong!).

Tolkien studies (like, I suppose, Lewis studies?) originated from (mostly) work by medievalists and folklorists during the 1960s-70s, using the theories that were current at the time, which I suspect was mostly New Criticism with a lot of heavy reliance on Biblical and Classical material (which I’m happy to call theories since I’m an atheist).

Theories changed over time. Disciplines changed over time. New “generations” of academics got trained.14 Lots of Stuff happened, and here we are in 2023, and the whole debate about “theory” has been a part of The Culture War(s) in the U.S. for decades!

General Niggles

What can linguistic theory, in-depth political science questions, or speculative world-building scholarship (emphasis added) teach us about Lewis’ fiction?

Well, this quote gives me a few more theories to add to “linguistics and medieval studies,” adding “in-depth political science questions” and “speculative world-building scholarship” to the list to make four. Still, the list ignores a number of contemporary critical theories.

I have no idea what Dickieson means by “in-depth political science questions” unless he, like others, just assumes anything to do with race, class, gender, sexuality is “political” and thus from “political science? Maybe? He does include “identity studies” (often called “identity politics”)15 as one of the “reasons for resistance to theory" (the other reasons are not specific theories ). "Speculative world-building scholarship" is the only one I recognize: heck, Dimitra Fimi and Thomas Honegger recently edited a great book on "sub-creation" and worldbuilding in Tolkien!

Here are the reasons Dickieson gives for the Lewis scholars’ resistance to “theory”16

1) following Lewis in resisting certain kinds of reading approaches (like psychological approaches or the conversation in The Personal Heresy that actually helped stimulate the “New Criticism” theory movement);

2) a conservative resistance to identity studies among some Lewis scholars;

3) the elitist nature of the literary theory conversation itself; and

4) theoretical conversations about Lewis’ work that have not always read Lewis well or that aren’t evidentially based.

I believe Dickieson is correct in the reasons he gives for Lewis scholarship's resistance to some specific critical theories. I say "believe" because I trust his knowledge of Lewis scholarship (and Lewis scholars!) and because the little I have read in Lewis scholarship and Inklings scholarship supports Dickieson’s reasons.

My niggle is with the idea of Tolkien scholars being more accepting, or less resistant to Bugbears. It is the same niggle I used before: there are a larger number of scholars, a greater variety of disciplines, using lots of different theories and theorists (some of which I knew nothing about until I heard my friends’ presentations or read their essays—wow, life-long learning is a Cool Thing, you know!). It is probably easier for smaller more homogeneous groups to resist.

However, while I know some individuals or groups in Tolkien studies share this resistance, but, presumably, unlike Lewis studies, there are a growing number of us who not only do not resist but in fact have been trained in the various Bugbears, as I discussed in my Part 2. Thus, while I think all four types of resistance appear in Tolkien studies as well, they do not dominate to the extent that apparently happens in Lewis studies.

As far as I know, Tolkien shared Lewis' resistance to some of the critical theories that were being used during his lifetime, especially psychoanalytical theory. I share that dislike/distrust of psychological/psychoanalytical literary studies in part because too often the focus shifts to analyzing the author in ways I find invasive and am very much uncomfortable with (if it comes to that, I am not particularly happy with some biographical approaches to Tolkien’s literature for the same reason).17

For a great exploration of Tolkien's position on critical theories (he wrote things that implied he was sort of against them all, especially applied to his fiction), which several Tolkien scholars think has hampered the development of Tolkien scholarship because people read his criticism of criticism and feel constrained to avoid it, I strongly recommend Sherrilyn Branchaw’s excellent essay, “Contextualizing the Writings of J. R. R. Tolkien on Literary Criticism.”18

Now on to the specific Tolkien scholars who resist Bugbears postmodern theory!

Drout and Wynne

When I discussed Drout and Wynne’s bibliographic essay in my MythCon talk, this is how I described it:

In 2000, Michael D. C. Drout and Hilary Wynne published an extensive and authoritative essay accompanying their thirty-page bibliography of Tolkien scholarship from 1984-2000, starting from when Johnson's ended. Their essay, "Tom Shippey's J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century and a Look Back at Tolkien Criticism Since 1982," identifies and addresses two related problems in Tolkien criticism: first, the tendency of Tolkien critics to not read the published criticism which leads the second, the repetition of certain basic arguments. They identify other bibliographic resources (I learned about Judith Johnson's book from this essay!) and analyze the scholarship from Shippey's first book to the time of their essay. They discuss the state of work on major topics in Tolkien scholarship: textual and manuscript history, source studies, themes of good and evil, Tolkien's "Mythology for England," and then go on to identify weaknesses and gaps they would like to see addressed in future Tolkien criticism. The weaknesses they identified include "defending Tolkien against his detractors," (113) and the "mocking of Tolkien fandom" (123). The gaps in the scholarship which need filling are, most importantly, stylistic analysis and applying contemporary socio-historical critical theories that involve consideration of constructions of race, class and gender to Tolkien's work although they seem somewhat dubious about those approaches. They also argue that good critical work requires studying The History of Middle-earth.19

This summary’s purpose was to accurately describe (as neutrally as possible) the main arguments in an impressive work of scholarship for my audience at the conference, some of whom were probably not familiar with it. I enjoy reading good bibliographic essays; not all people do!

I did not, for that talk, or the other times I have cited various of their arguments (and I *often* cite this essay) go into the niggles I have with their their conclusion, which is titled "Quo Vadis," and which, like all good conclusions for academic essays, provides suggestions on what future Tolkien scholarship could or should look like (and what types of scholarship to avoid) as well as restating the major argument of the essay.

“Quo Vadis” is ten paragraphs long (a substantive conclusion to a long and useful essay).

The first two paragraphs consider whether Tolkien scholarship should engage with what they call the "laundry list" of "race, class, and gender.”

From the opening of “Quo Vadis”:

A criticism that avoids most of the more commonly discussed issues in contemporary literature is simultaneously refreshing and frustrating. One breathes an enormous sigh of relief at being able to read article after article without hearing repeated the litany of "race, class, and gender" (or additional items added to this familiar laundry list). On the other hand, Tolkien’s work is ripe for some of the historico-literary analysis opened up by the burgeoning of theoretically complex and self-conscious scholarship in the 80's and 90's. Furthermore, Tolkien’s works challenge many of the comfortable assumptions made by "theory" and its practitioners, and can be used to debunk many of the sprawling truth-claims of theoretically centered critics.

Tolkien critics should continue to remedy the flaws in contemporary criticism by addressing issues that it ignores. It seems that the world hardly needs more articles on race, class, and gender, but ignoring these topics creates a situation where Tolkien critics and other literary scholars have nothing to talk about. Tolkien critics thus marginalize themselves and their subject (intentionally or otherwise) when they ignore issues important to contemporary literary studies. Truly the lack of serious, informed discussion of Good and Evil in contemporary mainstream literary criticism is a serious blind spot,33 but the metaphysical discussion of Tolkien’s works seems to have taken on a life of its own, to the detriment of literary study (pp. 121-22).

33 Which may explain why so much misguided criticism has been directed towards the Harry Potter books, which also deal with good and evil.

I would call that resistance!

The two opening paragraphs are followed, rather abruptly, by a change in topic to the sort of scholarship that, from their diction and tone, Drout and Wynne *really* want to see happen as well as what they really do not want to see (mostly anything that is not “literary” in nature—nothing on fandom, nothing about the work’s popularity) now that we’re past the dreary drudgery of the laundry-list. Of course, there is no Intellectual Police Unit to arrest scholars who write about theories or topics that other scholars do not like (though in the U.S. today, it seems more and more likely that some governors and legislatures are trying to pass laws to shut down Bugbear theories and programs).

The third paragraph opens with the claim that the “biggest failing in Tolkien criticism, however, is its lack of discussion of Tolkien’s style, his sentence-level writing, his word choice and syntax” (p. 122). Drout has been working on addressing that gap in his own work (and I’ve done some of it myself!). I’m all for stylistics — but there are many other gaps in Tolkien scholarship beyond the stylistic question which they discuss in some detail. Other things they want to see are more scholars using The History of Middle-earth, and, repeating their main point, more scholars in the future paying attention to what has already been published.

After their bibliographic essay, they provide a selected bibliography (they explain their principles in the introduction to the bibliography) of sources that they believe are of the best quality and should be read. I do not agree with the idea that only the “best” scholarship should be read — not that we can agree that easily — but my disagreement is because of my cultural studies approach.

My first niggle with their conclusion all spring from how they deal with the concept of “theory.” I think that Drout and Wynne’s ideas about theory are similar to what Dickieson says about Lewis scholarship’s response to theory.

Drout and Wynne's use of quotation marks around "theory" to specify writing about "race, class, and gender" in Tolkien as opposed to the not-theories such as metaphysics and stylistics is similar to Dickieson’s praise for “linguistics and medieval studies” as opposed to the bad/bugbear theories. I would argue the major distinction being made in both cases is not about THEORY vs “NOT-THEORY” but about the acceptable vs. unacceptable theories, the good vs. the bad, specifically, as I develop below, the “universal” vs. the “political.”

My impression is that Drout and Wynne, while they acknowledge the necessity for some Tolkien scholars to engage with the "laundry-list of theories," they are not able or willing to discuss how that engagement might work compared to the previous reliance upon, well, good theories? Un-Postmodern theories (retreat to Modernism?)

In the past, citing their bibliographic essay, I have paraphrased the basic argument of the first two paragraphs of the conclusion to draw upon their essay's authority to support my argument about the need for more Tolkien scholarship on "race, class, and gender." Under gender, I include sexuality, another controversial topic in Tolkien studies that has met with resistance, but that’s another whole post. Or ten. Or more.

Previous to this post, I have never engaged with the problems of how they dismiss a body (bodies?) of contemporary work dealing with oppression and marginalization in Anglophone history and culture as a "laundry list,” or their wholesale dismissal of undefined “post-modern” theories, at least not in my academic writing. I have ranted a bit in conversations, and in my fandom journal on Dreamwidth.

Years later, Drout, in a publication based on his Guest of Honor speech at MythCon, was even more direct about his distrust or rejection of Bugbear theory and actually gives a few defining characteristics of post-modernism (if it really exists!).

Put another way, Tolkien's work is kryptonite for weak literary theories. A really simple test of any supposedly brilliant literary theory is to put Tolkien's work in it. If the theory breaks, then the theory wasn't that good. So far Tolkien's work destroys just about every literary theory from the past 30 years. So you may not be surprised that I reject (mostly) a current minor industry in Tolkien studies: claiming that Tolkien really was post-modernist. That project is in most ways an extension of Shippey's approach that I've discussed above, and it works like this:

• Here's what some post-modernist theory says is good (meta-narrative, creating a whole world, invented documents and textuality, etc.).

• Tolkien does this.

• Therefore Tolkien is good and a post-modernist.

I think the approach is fundamentally misconceived. Not that there's no comparison between Tolkien and post-modernism or modernism, but it's kind of silly to go down this road too far. Tolkien just wasn't doing the things that writers like Donald Barthelme or Dom Dellilo or Angela Carter or Robert Coover were doing, and that's OK. You can point to frame narratives and meta-textual relationships all you want, but Tolkien and Italo Calvino or Umberto Eco are fundamentally different. Post-modernism, if there's even such a thing, is about irony (pp. 19-20)

Drout, Michael D. C. "'Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics' Seventy-Five Years Later'" Mythlore, vol. 30, no. 1/2, Fall/Winter 2011, p. 19.

Drout’s rhetoric moves from a fairly broad sense of Tolkien “destroying” (how?) “just about every [‘supposedly brilliant’] literary theory from the past thirty years” (so, 1981-2011?), to the narrower focus on Drout’s dislike about some recent publications “Tolkien really was post-modernist.” And, yes, a number of essays/collections have explored this idea although they do not all agree, or define postmodernism the same way.

My second, or perhaps a subset of my first, niggle is that I have no idea how a “theory” gets broken. Scholars using or misusing theories to produce shoddy work? Sure, happens all the time. But that’s not more “breaking” the theory than a bad adaptation (fill in your text of choice) of one of Tolkien’s novels “breaks” the novel, surely?

When I call myself a postmodernist scholar (when in company with medievalists), the meaning of the word when I use it (and I always define it) is "someone who draws primarily on the literary/critical theories that developed during the last half of the 20th century” which primarily means cultural studies, feminist theory, queer theory, intersectional & critical race theories, though in recent years I’ve added a bit of phenomenology but it’s QUEER phenomenology (because while I do not know how theories can break, I do know how they can get together, rock and roll, and spawn amazing baby theories!).

And I plan to keep doing what I have been doing, or even more so, despite disapproval by senior scholars trained in other periods and fields, just as I plan to keep reading their work in order to appreciate the good work they do in spite of their prejudices.

But after forty or so years of these kind of cultural conflicts, and seeing how much the animosity and violence of the “culture war” has increased the last few years, I am getting pretty tired of them.

In recent years, inspired and influenced by Drout and Wynne’s essay, I have been doing what I call thematic or focused bibliographic essays, in part because I think there is so. much. scholarship. published on Tolkien that nobody can read it all, or evaluate it all, or pretend to be able to identify the “best” when it’s so diverse in terms of theories and methods.

The first essay was "Race and Tolkien," in Tolkien and Alterity edited by Christopher Vaccaro and Yvette Kisor. The second, on scholarship about female characters in Tolkien, was published in Perilous and Fair: Women in the Works and Life of J. R. R. Tolkien, edited by Janet Brennan Croft and Leslie Donovan. I had great fun analyzing the scholarship in both cases and teasing out a meta-analysis.

Based on these projects, I have the sense is that there was more work done on female characters (although not always, as I note in the essay, with a feminist perspective or using feminist theories), and that this sub-field began earlier than work done on race and racisms, or on sexuality and queerness.20

Although I know one must be cautious in making such claims: a recently published essay, “The Wretched of Middle-earth: An Orkish Manifesto,” by Charles W. Mills, an Afro-Jamaican philosopher of race, was just published. Although it was written in the 1980s, Mills could not get it published as his literary executor, Chike Jeffers, and David Miguel Gray explain in this Introduction. Mills’ essay is a radical shift in the sub-field of “Race and Tolkien” (chronologically, thematically, theoretically, and every other way!).

My sense is that while the resistance to Bugbear theory seems to be fading in Tolkien studies, I think it has been replaced by a sort of tolerance. I do not perceive "tolerance" as a positive attitude. “Tolerance” is willing to shrug and let those of us doing this weird work go ahead and do it, and publish it if we can (somebody has to do the laundry), but disagrees with it, or refuses to see it as related to the REAL important work on the "universal/timeless" topics which informs their scholarship (metaphysics! stylistics). Their theory is universal; our theory ("identity politics") is political.

The tolerant can thus avoid reading/engaging with the political scholarship because they do not "do" race, gender, or sexuality: they literally do not *see* it in Tolkien's legendarium.21 The assumption underlying this tolerance is that some theories are political and some are not. I can think of no better response to that dismissal than to quote Sue Kim, from her brilliant essay on Peter Jackson's film, when she observes that:

critics, scholars, and filmmakers can and do associate Tolkien's (and Jackson's) works with specific nineteenth and twentieth-century political issues, such as industrialism and modern wars, while disallowing applicability of other contemporary political issues such as race and gender (881-882)22

Yep, war! Universal! Timeless! Not in the least Political or about “identities.” Nothing POLITICAL here, keep moving, please.

Kim's discussion of the restrictions on what "political" issues are universal enough for Tolkien scholars to consider appropriate is similar to my sense of the restrictions on kinds of "theory." There are universal topics, or themes (Good, Evil, metaphysics, writing style, industry, the World Wars), and then there are the theories often dismissed as "identity politics" which are a "laundry list" of topics that consider difference and Othering in the constructions of various hierarchies.

The most significant problem I see in Tolkien studies — which is not unique to the field — but is a structural characteristic of all of academia in the United States (the only nation I can speak about with authority) is the Whiteness of both academic and fan cultures. That is the problem we need to be working on.

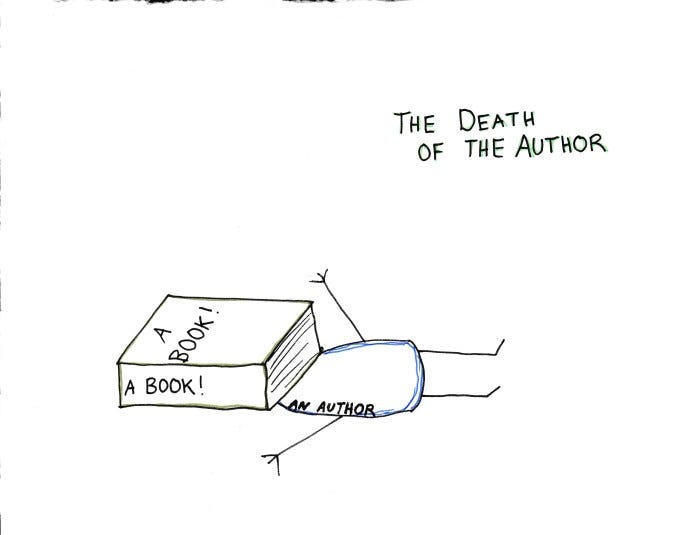

Coda: Bugbears Killed the AUTHOR

One of the theories I see called out quite often as the ultimate example of Bugbears is Roland Barthes' "Death of the Author.”23 People who have never read Barthes hate the theory. They remind me of all the English profs I knew back in the 1970s who had never read sf or fantasy, including Tolkien, because they knew it was bad from what they'd heard. Sitting in their classrooms listening to what they said was the first realization of fallibility of my professors (I was raised by a professor, so you would think I could figure it out earlier! More of this is the fourth and final part of this series!).

For those who do not want to read the summary linked above, here is an illustration from the delightful blog by the Master of Literature “Pictures of Theories” series:

The way Barthes' argument is simplified/literalized (in the popular imagination, not relying particularly on what he actually wrote, mind you) has made it the stand in for all that many people consider wrong/bad about "literary theory" (though that concept is probably in a dead heat for first place with "cultural Marxism" AKA The Frankfurt School).

“Postmodernists” in this view are metaphorically assassinating authors. We are accused of perverting or corrupting them, with the result they are “spinning in their graves” (if they are actually dead which, you know, Tolkien is), by denying them any intentionality (ignoring the fact Barthes was talking, in part about "Author" as a theoretical, or social construct, that has specific historic roots, not individual human beings).

What I have observed over the years is that many of the most vociferous objectors to the claim that it is impossible to make any claim about any author’s intentionality as being the sole authority about the correct meaning of a text is that said objectors are awfully quick to speak for the “author” as if they have some pipeline into the (usually dead) author’s brain. The older I get, the more irritated I get by that tendency, so I had to respond to a recent example of what I call the religious/allegorical reading of Tolkien: since Tolkien was Catholic, there is only one way to correctly interpret his work which is [INSERT BIBLE].

The other element that I think bothers those who object to Barthes’ theory (and cultural and reception studies generally) is the way in which the theory notes the agency of readers, arguing that the “meanings” of texts are created by the reading of the text. Giving readers so much agency might, I guess, be seen as undercutting not only the authority of the “author” but also (I speculate snidely), the authority of the “Literature Teacher” (another social construct).

Join us—we have COOKIES nom nom nom nom!

"On the Shoulders of Gi(E)nts: The Joys of Bibliographic Scholarship and Fanzines in Tolkien Studies." Mythlore, vol. 37, no. 2 , Article 3. https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol37/iss2/3.

We would have to start with basic definitions: he specifies “literary” theory while I tend to use the phrase “critical” theory (which can include theories applied to “literature” — however literature” is defined which can also be tricky — but can equally well include other types of texts — adaptations, transformative works, games, etc.). Here are some basic resources for those interested in the history and development of “theory”:

Literary Theory in North America by Patrick Colm Hogan

Literary Theory by Vince Brewton

A review by Leon Golden of A History of Literary Theory and Criticism from Plato to the Present by Rafey Habib,

Critical Theory by James Bohman

Literary and Critical Theory by Eugene O’Brien

Dickieson describes this phenomenon as Lewis scholars tending to offer each other:

warm, glowing reviews nearly across the board. They are well written and respectful, offering a point or two of rebuttal or correction, but they are rarely reviews that really challenge the work at its core or in detail. When they do, it is sometimes because the author under review has been tempted to co-opt or misinterpret Lewis–so the reviewer is operating on an instinct to protect Lewis. ("The Beautiful Problem of Scholarly Friends").

I have a small niggle about this point that is more or less the same as the niggle in my previous post: I think the same thing happens in Tolkien studies but, because the number of scholars publishing is (relatively) larger, it seems likely that there are groups/cliques that are more focused on each other’s work and their friendship while ignoring the rest of the scholarship. Add the greater diversity in theories/methods, and the result is more challenging reviews (and, I think, on occasion, more of what I call ‘attack’ reviews that are based on dismissing a theory or approach rather than engaging with the reading based on it).

To be fair to medievalists, I have to note that, as discussed previously, in Part 2, note 11, a lot of the BUGBEAR theories are turning in up in medieval studies these days: medieval studies today is not Tolkien’s medieval studies as Kathy Lavezzo so aptly points out in “Whiteness, medievalism, immigration: rethinking Tolkien through Stuart Hall.” Of interest to Tolkienists is that Stuart Hall, the major founder of cultural studies, was a student of Tolkien’s who wanted to work on medieval literature—but left after Tolkien would not approve Hall’s idea to work on William Langland!

I gave myself the present of a year’s subscription to the OED this year!

I love the OED (and loved it even before I knew about Tolkien working on it). And much of what I love are the quotes that (in my experience) many people gloss over as they pull out a definition to use to support their argument. Given that words change meanings, and the OED (while not perfect! nothing in this world is perfect) provides chronological evidence of how people (whose work was published and still available to researchers) actually used those words and how those meanings changed — I mean, it’s incredible!

The most common common theories under attack generally in U.S. conservative and some liberal circles since (in my memory and personal experience) the 1980s are: FEMINISM, GENDER THEORY, QUEER THEORY, QUEER THEORY, IDENTITY POLITICS (focusing usually on theories relating to gender, sexuality, or, the current bugbears of the fascists, CRITICAL RACE THEORY). These specific theories often get subsumed under POSTMODERNISM, CULTURAL MARXISTS, or, increasingly these days dismissed as “WOKE.” No matter what the term used to dismiss them, the message is “the monsters are destroying WESTERN CIVILIZATION11!!!!!.” POSTMODERNISM seems to be the Biggest Bugbear in Tolkien studies, although surprisingly few of the critics who claim it is ruining the scholarship/Western Civilization take the time to define “postmodernism” (and yes, there are some different definitions, but that requires a critic picks the one that is the best example of what, specifically, they object to and, ideally, provide some actual examples, you know, evidence, as opposed to vague rants).

The two essays are: Drout, Michael D. C. and Hilary Wynne. "Tom Shippey's J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century and a Look Back at Tolkien Criticism Since 1982," Envoi, vol. 9, no. 2, 2000, pp 101-134.

Drout, Michael D.C. ""Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics" Seventy-Five Years Later,", Mythlore, vol. 30, no. 1, article 2, 2011, pp. 5-22.

Jane Chance, according to her Wikipedia entry, was born in 1945 (ten years before I was born): she is retired, as am I. Neither Chris nor Yvette has gained enough “notability” to be the subject of Wikipedia articles, but I know them both personally, and they are significantly younger than I am: neither are close to retirement. I would consider them to be in a different generation than Jane (all are medievalists).

As I discuss in my Part 2, Note 5, the earliest Tolkien bibliographic publications incorporated what I call fan scholarship (written by fans for fans in fanzines but using the critical and intellectual tools people learn in school) as well as articles in general periodicals along with work in academic journals which was pretty thin on the ground at the start. Sadly these bibliographies are out of print (but can be found in some library collections or archives and for sale on used book sites although not always for a reasonable price): the bibliographers are Richard West and Judith Johnson. The Tolkien Society and the Mythopoeic Society started out as “fan clubs,” but over the decades have integrated more academic activities (in part because some of their members, like Richard West, became scholars over the years). Besides the “academic scholars” (those who earn a living by working in academic jobs often but not always faculty positions), Tolkien studies benefitted immensely from independent scholars, meaning people who do scholarship but without the support of a permanent academic position, often supporting themselves in different jobs (everybody knows the amazing work by Douglas Anderson and John Rateliff). and I suspect independent scholars will continue to contribute in the future, especially given the acceleration of budget cuts due to the pandemic and the increasing attacks on tenure in the U.S. As a retired faculty member who refused to apply to emerita status, I am an independent scholar (not affiliated with any university).

My favorite summary of the different definitions of “queer” developed in queer studies is by Alexander Doty, in his 2000 book, Flaming Classics: Queering the Film Canon (Routledge 2000). One of the most important elements he points out is that “queer” is not always “radical, progressive, or even liberal”!

One caveat about the list below: saying something is queer according to one of these definitions does not necessarily indicate a radical, progressive, or even liberal position on gender, sexuality, or other issues. For example, the queer work a straight person does in writing about a gay- or lesbian-themed film might express a conservative or normative ideological position. Some would like the term 'queer' to be reserved only for those approaches, positions, and texts that are in some way progressive. But, in practice, queerness has been more ideologically inclusive. Hence there is a need to discuss the politics of queerness carefully and specifically and not just assume that to be queer is to represent a position somewhere on the left.

Queer/queerness has been used:

1 As a synonym for either gay, or lesbian, or bisexual.

2 In various ways as an umbrella term

a to pull together lesbian, and/or gay, and/or bisexual with little or no attention to differences (similar to certain uses of "gay" to mean lesbians, gay men, and sometimes, bisexuals, transsexuals, and transgendered people).

b to describe a range of distinct non-straight positions being juxtaposed with each other.

c to suggest those overlapping areas between and among lesbian, and/or gay, and/or bisexual, and/or other non-straight positions.

3 To describe the non-straight work, positions, pleasures, and readings of people who don't share the same "sexual orientation" as the text they are producing or responding to (for example, a straight scholar might be said to do queer work when she/he writes an essay on Gus Van Sant's My Own Private Idaho, or someone gay might take queer pleasure in the lesbian film Desert Hearts.)

4 To describe any nonnormative expression of gender, including those connected with straightness.

5 To describe non-straight things that are not clearly marked as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transsexual, or transgendered, but that seem to suggest or allude to one or more of these categories, often in a vague, confusing, or incoherent manner (for example, Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs or Katharine Hepburn's character in Sylvia Scarlett).

6 To describe those aspects of spectatorship, cultural readership, production, and textual coding that seem to establish spaces not described by, or contained within, straight, gay, lesbian, bisexual, transsexual or transgendered understandings and categorization of gender and sexuality—this is a more radical understanding of queer, as queerness here is something apart from established gender and sexuality categories, not the result of vague or confused coding or positioning (I would contend that Jack Smith's Flaming Creatures is a queer avant-garde film by this definition) (pp. 6-7)

Additional thing I learned by hanging out with medievalists: in the popular imagination is that people equate “Middle Ages” with Europe, but all world civilizations had medieval periods: Medieval China for instance, as well as Medieval India, ditto Medieval Africa. Plus, there’s a whole new field (somewhat controversial, but what isn’t in academia), on “medievalisms” — the interpretations and representations of “the Middle Ages” during later historical periods. And there is a series on Global Medievalisms.

Some of the younger generation of scholars (who do include non-traditional students in terms of age as I was) have had the chance to take courses in Tolkien, or Jackson, or both, on undergraduate and graduate levels. I taught such courses myself before I retired. But when I was a student, nobody in my Master’s or doctoral program taught Tolkien or sf or fantasy. There was one science fiction course in my undergraduate English program which, the professor quellingly announced the first day, would cover only the sf which met the (his?) criteria for Literature (BIG L!), none of that popular stuff (specifically pointing to Asimov and Heinlein as popular/trash). The Literary SF was of course all by Dead White Men (often European). And I rather enjoyed the class, but taught a much different set of texts when I had the chance to teach sff.

I have a whole rant about how the people dismissing "identity politics" are mostly white, middle-class, cis, and straight men and (some) women. “Identity politics” has been built into the “American” since the start in terms of classes of human beings denied the status of human and denied the rights the elite white men reserved for themselves. See: Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination!

Am I the only one who wants to intone, “Resistance is futile”? Probably not. I think I would rather be a Bugbear than a Borg though.

Criticizing a theory is one thing: but conceptualizing "theory" (or, let’s be honest here, only the theories one does not agree with/like/know very much about) is a short step away from dehumanizing the people who work with those theories, and we see more and more of those attacks happening today.

Branchaw, Sherrylyn. "Contextualizing the Writings of J.R.R. Tolkien on Literary Criticism," Journal of Tolkien Research, 2014, Vol. 1, iss. 1, Article 2. https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol1/iss1/2

Drout, Michael D. C. and Hilary Wynne, "Tom Shippey's J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century and a Look back at Tolkien Criticism since 1982,'' Envoi 9, no. 2, Fall 2000, pp. 101-167.

The only bibliographic essay on queer approaches to Tolkien, meaning “alterity,” is Yvette Kisor’s “Queer Tolkien: A Bibliographical Essay on Tolkien and Alterity,” published in Tolkien and Alterity.

Shippey’s Author of the Century does a lot of great stuff—I have assigned it or parts of it in a number of classes — but he never mentions any of the female characters as far as I can tell. Jane Chance’s Queer Creature which emphasizes Tolkien’s feminisms at least devotes one whole chapter (out of nine) to the female characters and women in Tolkien’s scholarship.

Sue Kim. "Beyond Black and White: Race and Postmodernism in The Lord of the Rings Film." In Hughes, Shaun F. D., ed. "J. R. R. Tolkien Special Issue." Mfs: Modern Fiction Studies, vol. 50, iss. 4, Winter 2004. pp. 875-907.

I have looked at some of the other pictures at the Master of Literature’s blog — they are not all litcrit theories — and I have to admit the Deconstruction one is pretty fantastic too (BIG REVEAL: I have never understood this theory, had a helluva time trying to teach it, told my students I never understood it, and generally dislike it immensely — but this is the first time I have ever ranted about it in print — and I would never do so in an academic article or claim that it was somehow all bad because I do not understand or like it). There are a number of theories I dislike (including archetypal theory by Campell and Jung), but I have seen good scholarship produced by scholars using those theories!